An atheist, a feminist, and a rabbi walk into a bildungsroman—

A couple years ago, Barry was wondering if he’d ever do a comic book again.

Today, Hereville’s written up in the Washington Post.

(And while we’ve got it up, ponder a moment the volatility of this brave new digital world: that two-year-old post of his is already showing the wear and the tear. Not that I’m any better: my links rotted away in the interim. The blog post he was talking about is now here.)

—It is presumed that all you habitués of the pier subscribe to Girlamatic already, the better to get your weekly fix of Dicebox. But for this week, the first 20 pages of “How Mirka Got Her Sword” are available for free, so go, read, get hooked, subscribe. Hoopla, Barry!

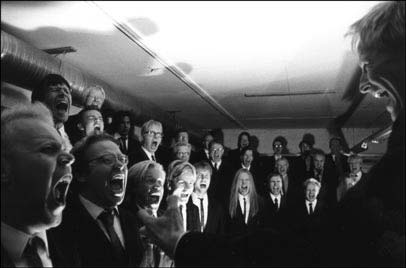

Ladies and gentlemen—

—the Finnish Men’s Shouting Choir.

Things to remember.

I’d never suggest How Much for Just the Planet? was in the same league as Singin’ in the Rain; not as sublimely silly, for one thing, but neither is it so athletically earnest. —But it’s all a matter of degree and not of kind: I would not hesitate, would in fact leap to recommend it, as an antidote to the sort of day I’ve had. Splash of Maker’s Mark and sleepy kitten optional.

(When the old skool Klingon security officer Happy Gilmores his first tee-off to within thirty yards of the green, you will have to pick the kitten back up and apologize most sincerely for having giggled him off your chest and onto the floor. I’m just sayin’.)

Utterly unrelated (except in all the ways it’s not), you have got to get yourself some Lady Sovereign. Read here, here, and, oh, here; then download here and, oh, shit yeah, here, while you still can.

Once more, Patrick Nielsen Hayden saves the day.

Well, he did. —I finished Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell a bit back, and enjoyed it quite a bit, finding the digressive length (both of opening acts and footnotes) muttered over elsewhere to be delightful and ultimately necessary: groundwork to build a proper floor from which to kick off into, well. To say much more would spoil; I’ll just note that magic is abominably tricky to pull off, and Susanna Clarke manages to step nimbly from Potteresque cantrippery to Lovecraftianesque occultiana (the latter as architected, perhaps, by Peake) while playing allegorical games on several levels: John Holbo reads it as philosophy, naturally enough; I read it as writing, with Norrell as critic to Strange’s writer, and if that explains why I still found Norrell the more sympathetic when all was said and done, well, it doesn’t make me any happier about it.

But: the day, and its salvation. While reading it, I’d perk up whenever I stumbled over its discussion elsewhere, like this Crooked Timber post, which led me to John Clute’s review, which I dropped like a hot potato halfway through, when I learned of a plot twist I hadn’t yet tumbled to. (Should have paid attention to those spoiler warnings.) Stung, I slunk back to the book, consoling myself with the idea that I would have seen it coming soon enough, and anyway, the gotcha is the least important part of a plot twist; otherwise, we’d all save time with Cliffs Notes. —What I hadn’t noticed was how the book had been spoiled on a more fundamental level: Clute, you see, tells us that Strange & Norrell is but the first book in a proposed series.

Which surprised me—the book is a long way off from your door-stopping wodge of extruded fantasy product, and though I couldn’t tell you how exactly it doesn’t step like a volume one, nonetheless, it quite clearly doesn’t; it carries itself neatly, of a piece, whole. —Now, this doesn’t prevent it from being volume one of a proposed series, any more than keeling over suddenly in the middle of a jungle prevents Cryptonomicon from being a single book, prequels notwithstanding. And series and sequelæ are pretty much a fact of life in the Beowulf game these days. So I didn’t question Strange & Norrell’s status as volume one of; even began reading it in that light (indeed, couldn’t help but), wondering how the story would go on from here, wondering which characters would play what roles the next time ’round. Wondering, but also worrying, even fretting, because Clarke pulls off her magic trick about the only way you can: by hinting, alluding, suggesting, glossing; by taking crucial bits for granted, by knowing when to let up, so the readers come the rest of the way themselves. And because Clarke’s enterprise is to thin the walls between worlds and bring the magic back, the only place she can go is where Strange & Norrell stops: right up to the gates themselves, or maybe a step or two beyond. The stuff Clute presumes would fill out the next two volumes of Clarke’s three-book contract—the stuff, in fact, he seems to think is missing from the story—would be too much; would leach the magic away by nailing it down. Those gaps, I thought, were there for a reason, and while it’s hardly impossible that volumes two and three wouldn’t be worthless, still: they felt like they’d be mistakes. I began to resent the shadow they cast over what I was reading here and now. —There and then, rather.

So tonight I’m bopping about old posts and threads and decide on a whim to check on John Holbo’s midstream review, where I find this comment from the electrolit Patrick—

Allow me to presume on my small acquaintanceship with Susanna Clarke in order to tell you that John Clute’s assertion that Jonathan Strange was planned as the beginning of a series was entirely pulled out of John Clute’s ass. There is no such plan. Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell is a complete work.

Susanna has more recently said she might write a different novel with the same background, but it would not be about the same people. And yet people keep repeating Clute’s entirely erroneous assertion that the book is the start of a planned-out series à la Jordan, Martin, Donaldson, etc. It’s not, and it never was.

And it’s astonishing: not one word of the book I read has changed, and yet it’s suddenly so much better. What a wonderful trick! My thanks to you, sir; kudos and hosannahs.

Canary watch.

Remember galiel’s canaries? Americans United for Separation of Church and State has a one-click email thing you can send to your various elected representatives about four of them: the “Constitution Restoration Act,” the “Safeguarding Our Religious Liberties Act,” the “Ten Commandments Defense Act,” and the “Marriage Protection Act of 2003.” —Y’all don’t need a sermon, and we can argue the political expediency of Marbury v. Madison later: the names of those bills alone ought to be enough to chill you into whatever action you can take. (Hearing that Rep. John Hostettler (R-Ind.) has been paraphrasing Stalin—

When the courts make unconstitutional decisions, we should not enforce them. Federal courts have no army or navy… The court can opine, decide, talk about, sing, whatever it wants to do. We’re not saying they can’t do that. At the end of the day, we’re saying the court can’t enforce its opinions.

(Well, hell. That’s just an extra shiver.)

—Hat-tip to Majikthise.

And when we say everything changed—

Twenty-five years after Alvin Toffler coined the term “Prosumer” in his book The Third Wave, Consumer Anthropologist Robbie Blinkoff says the Prosumer is officially here to stay and that this holiday season is their coming of age. “Think of it as the coming out party for a new species, an evolution in a consumer mindset. It is now the producers—companies, manufacturers, marketers and retailers, who need to adapt,” said Blinkoff.

A Prosumer is part producer part consumer [sic]. Prosumers are engaged in a creative process of producing a product and service portfolio with guidance from trusted friends—the companies they’ve trusted for years and the new ones they’ve come to love.

Certainly Toffler’s prophesy was becoming a reality with mass computer consumption, Internet, Cable TV and digital technologies available, but Blinkoff, a Principal Anthropologist at Context-Based Research Group in Baltimore, says something dramatic happened to the Prosumer landscape that sped up the evolutionary process. That monumental event was 9/11.

“9/11 unleashed a full scale remapping of the cultural landscape. People were and are re-establishing their identities—their sense of who they are,” said Blinkoff. “And given that consumerism is at the core of our culture, its no surprise that we went to our culture core to help us regain our identity.”

—RedNova, “The Prosumers Have Arrived and Will Be Out in Full Force This Holiday Season, According to Context-Based Research Group,” via Purse Lip Square Jaw

For some value of “our.”

The state of the industry.

What’s that? I haven’t told you that all the cool kids are bookmarking the Comics Reporter, Tom Spurgeon’s new(ish) source for comics industry news and reviews? Oh. Sorry about that. I meant to, that’s for damn sure. Anyway, today he links to this Ninth Art diatribe on the current industry practice of relaunching struggling titles with a brand new issue number one, with an eye towards those last few folks left in the world who’ll buy any goddamn comicbook on the shelves, so long as it’s got a number one on the cover. —And I know I’ve told you before that no matter how badly the industry might be doing, the state of the art in comics has never been better, and I know that we’re in the midst of a long and painfully drawn-out shift from periodical pamphlets sold on a non-returnable basis through a tightly knit network of specialty shops to bound books and web-based content sold through a mix of venues yet to be determined, and I know the numbers you’re about to see reach back to the dim ’n’ misty newsstand days, when Spider-man tussled on a regular basis with Look and TV Guide, but hey—every now and then a little perspective slapped upside the head like a cold fish doesn’t hurt:

Everyone knows that the market is much smaller, but it’s worth throwing in a historical comparison to flag up the scale: when X-Men was cancelled in 1970, the final issue contained an editorial explaining that “the plain truth is that the magazine’s sales don’t warrant our continuing the title. We feel that the artists and writers involved can better devote their time to other projects, other characters.” Two inches below, the Statement of Ownership appears, revealing that the previous issue had a total paid circulation of 199,571. Dipping below 200,000 was disastrous in those days. Today, Identity Crisis is considered a hit with sales in the region of 125,000, and Fallen Angel hovers around the 10,000 mark. No wonder the publishers are more interested in licensing.

I mean, sometimes the state of the art just isn’t enough, as Spurgeon’s eulogy for the late lamented Highwater Books will tell you.

Atlas leans back everywhere.

You’ve seen it by now, I hope? —At the very least, you’ve seen the preview, and I bet you giggled at the bit where Frozone’s looking for his longjohns, which goes a little something like this:

FROZONE:

Honey—where’s my super-suit?

HIS WIFE:

Your what?

FROZONE:

Where’s my super-suit?

HIS WIFE:

Why do you need to know?

A helicopter explodes.

FROZONE:

We’re talking about the greater good!

HIS WIFE:

I am your wife! I am all the greater good you need!

Frozone, of course, gets his super-suit, and saves as much of the day as a sidekick can, with some stylin’ speedskating moves: the great power that necessitates the great responsibility he feels. (Well, that, and the adrenaline rush.) —Hooray for the greater good!

Now, there are some folks tut-tutting this flick for being excessively Randian. “The Incredibles is ‘brilliantly engaging,’ [Stuart] Klawans says—which makes it ‘more worrisome, if you lack blind faith in the writings of Ayn Rand.’” —Which reminds me of a minor strain of Trekkiedom that insists Spock’s bloodless Vulcan logic must in its particulars resemble Rand’s Objectivism, because, y’know, Vulcan logic is logical, and Objectivism is logical, so hey presto. Not entirely sure what those Trekkies do with the image of Spock slumped on the floor, his green Vulcan blood smeared melodramatically along the glass wall, huskily telling Kirk with maddening imperturbability that “it is logical: the needs of the many outweigh—”

Then, it’s not really my problem, is it?

Nor am I entirely sure how to apply a Randian reading to a superhero flick in which the superheroes end up right back in the obscurity from which they came, danger their only reward for pulling on the tights—okay, danger, and some small government help in dodging the occasional catastrophic insurance claim and class-action suit. And their pictures on the covers of magazines. And free bullet-proof supersuits. And the adulation of millions. —But aside from all that.

As with any superhero work, there are echoes and resonances, responses and repudiations of Rand and Nietzsche. That stuff’s built in, like the secret identities and the underwear on the outside: even if you try not to do them, you have to take the time to let the audience know you’re not doing them, which means you end up doing them. Whoops. —So, yes: there’s a there there in The Incredibles, sure, but mostly because it is what it is. Brad Bird wanted to tell a story with superheroes in it; along with that genre comes certain baggage; that he hauls it about without complaint does not mean he’s crafted a candy-colored piece of crypto-Randian propaganda.

For instance: to read the conflict with Syndrome, the villain, as a “class war” of Übermenschen v. Lumpen is to miss the whole point of his costume, his tropical island, his lava curtain, his expendable henchpeople, his Heat Miser hair, his zero-point energy gauntlets. Syndrome doesn’t want super powers. He’s had super powers ever since he was a wee tot: he’s the mad inventor, the kid genius, the gadgeteer: a super-powered archetype with a long and pulpy pedigree. What it is that Syndrome wants is to be a superhero—without, y’know, the pesky bother of all those superheroics. He doesn’t get the altruistic end of the stick; he just wants to shortcut straight to the adulation.

So Syndrome isn’t an unpowered drone with delusions of acting above his station. Syndrome’s an asshole.

Okay, how about when Bob Parr, née Incredible, bursts out with “They’re constantly finding ways to celebrate mediocrity!” Classic Ü v. L, right? —Except he’s griping about Dash’s “graduation ceremony”—for moving from fourth grade to fifth grade. It’s not the people, powered or un-, that are mediocre; it’s the experience. Bob’s railing at the insidious successorized insistence that every moment be special, everything be wonderful, that we’re always happy, no matter what, always game, always up for it, always closing, that we’re always safe and satisfied and sound: the awful logic that actually believes nine hours a day in a fluorescently buzzing cubicle end-running legitimate insurance claims really is a rewarding position that utilizes your talents and skillset in a meaningful fashion that best satisfies your life-goals.

(“If everyone’s special,” sneers Syndrome, whines Dash, “then no one will be.” —Yes, yes. I never said this was a slam-dunk.)

And then there’s the somewhat more grounded criticism of the family’s superpowers, and how they mimic and mirror and reinforce white-bread patriarchal family values, ew, ick: Dad’s hella strong; Mom stretches herself thin to keep up with everyone; the adolescent daughter just wants to disappear; tweener son’s a hyperactive blur—

Bird’s biggest achievement in The Incredibles is to have inflated family stereotypes to parade-balloon size. His failing is that, in so doing, he also confirmed these stereotypes, and worse. Helen mouths one or two semi-feminist wisecracks but readily gives up her career for a house and kids; women are like that.

Klawans again, and again he’s missing a point that superhero aficionados know in their bones—but, more shockingly, one that’s right there on the screen, one of the major themes of the movie, one he checks himself in the very next sentence: “they chafe at their confinement, like Ayn Rand railing against enforced mediocrity.” —Hell, Bill got it, even if he did crib it from Jules Feiffer:

When Superman wakes up in the morning, he is Superman. His alter ego is Clark Kent. His outfit with the big red S is the blanket he was wrapped in as a baby, when the Kents found him. Those are his clothes. What Kent wears, the glasses, the business suit, that’s the costume. That’s the costume Superman wears to blend in with us. Clark Kent is how Superman views us. And what are the characteristics of Clark Kent? He’s weak, unsure of himself… he’s a coward. Clark Kent is Superman’s critique on the whole human race, sort of like Beatrix Kiddo and Mrs. Tommy Plumpton.

Helen Parr doesn’t give up her career for a house and kids because women are like that; she gives it up because a spate of lawsuits drives the supers into hiding, and so she tries to live up to the normal idea of what women are like—and it fails, miserably. Bob’s miserable when he tries to carry the weight of his family on his back alone. Violet blossoms when she’s able to take direct action to save and protect her parents. Dash—well, let’s give Dash props; he knows what he wants all along, and when he finally gets it, it’s a blast of sheer, unadulterated joy that leaves you whooping and hollering and forgetting for the moment the distressing bodycount. The triumph of the movie is seeing the family set aside its constraining, restraining roles and work together to get something done: rather less patriarchal than the good Dr. Dobson might want, I should think.

Of course, at the end of the movie, the status quo is mostly resumed: the Incredibles return to incognito, and though Dash gets to run track, he can’t do it full-out, y’know? Rational, egotistical Objectivism is not followed to its seemingly logical conclusion: they don’t end up living in their supersuits, imposing the super-powered diktatoriat that is their Nietzschean due. —Their secret identities are lies, yes, but not lies to be repudiated: they’re roles, to be put on and taken off as needed—necessary compromises we all must negotiate with the expectations of the world around us. The Parrs’ mistake was to think that the Breadwinner or the Homemaker were somehow more real and true than the supersuits.

No, if you want to read The Incredibles as some sort of Randian parable, then it becomes a tragedy. Syndrome is our protagonist: the genius inventor whose fabulous wealth was created—rationally, egotistically—by the focussed application of his singular talents. He dreams of a world in which cheap, zero-point energy puts the mythic powers of a select few within the reach of us all—the ecstatic epiphany of Flex Mentallo; “Harrison Bergeron” run in reverse, like some madcap technicolor dream. —But here come the Incredibles, representatives of that select few, who destroy his wealth and smash his dream and grind him back into the dust, hogging the glory all to themselves: call it Incredible Planetary, if you like.

“If everyone were special.” —There are some problems it might be fun to have. Y’know?

The war of us and them.

And you know, I really ought to be working on the next watchmaker bit. I started revamping that old thing because I’d thought I might have a little time to post this week, but had no idea what I’d say.

Funny how things work out.

Anyway, Josh Lukin writes to let me know that “The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism” ain’t necessarily all that, but “...Three, Two, One, Contact: Times Square Red,” now there’s a fuckin’ essay, which reminds me that I still haven’t dug my copy of Times Square Red Times Square Blue to the top of my tottering pile, so I do, and I open it to “Red,” and here, let me write out the first two paragraphs that I saw while we still have some small shreds of Fair Use left:

The primary thesis underlying my several arguments here is that, given the mode of capitalism under which we live, life is at its most rewarding, productive, and pleasant when large numbers of people understand, appreciate, and seek out interclass contact and communication conducted in a mode of good will.

My secondary thesis is, however, that the class war raging constantly and often silently in the comparatively stabilized societies of the developed world, though it is at times as hard to detect as Freud’s unconscious or the structure of discourse, perpetually works for the erosion of the social practices through which interclass communication takes place and of the institutions holding those practices stable, so that new institutions must always be conceived and set in place to take over the jobs of those that are battered again and again till they are destroyed.

That right there is a model of how things are and what happens to them as we go along. —Here’s another:

An evelm philosopher once wrote: “Almost all human attempts to deal with the concept of death fall into two categories. The first can be described by the injunction: ‘Live life moment by moment as intensely as possible, even to the moment of one’s dying.’ The second can be expressed by the exhortation: ‘Concentrate only on what is truly eternal—time, space, or whatever hypermedium they are inscribed in—and ignore all the illusory trivialities presented by the accident of the senses, unto birth and death itself.’ For women who adhere to either position,” this wise creature noted, “the other is considered the pit of error, the road to injustice, and the locus of sin.”

And one’s from an essay and the other’s from a science fiction novel and it’s not like it’s either the first or the second and there aren’t other ways of looking at things, I mean, for God’s sake, they aren’t even mutually exclusive, and I know you might quibble with this or that aspect of the one or the other, and that what I’m about to do is unfair and even brutally reductionist, but still: take the one, and the the other, and hold ’em up against our current situation, the great divide, the Blue and the Red.

Which does a better job of limning the struggle we’re actually in, and the actual sides that have lined up to join it?

That said, what tactics now suggest themselves? Seem more useful? Counterproductive? Downright destructive?

Quis tulerit Gracchos de seditone querentes?

So Joshua Micah Marshall links to the Daou Report, which was highlighting a Corner post by Ramesh Ponnuru, and now I have another Lewis Black earwig wreaking havoc with my equilibrium:

The risk is that liberals’ moral arguments are peculiarly prone to coming across as self-righteous and moralistic.

And yes, I know he means it in the “addicted to moralising” sense and not merely in the “pertaining to or characteristic of one who practices morality” sense, but hey: he left the door open. And it’s a lovely little piece of snark to walk away with, isn’t it? Our moral arguments are hampered by an actual morality that we insist on applying to ourselves—and thus, by extension, anyone who’d join our club.

Their moral arguments consist mostly of ganging up to tell some convenient Other on the margins over yonder that they’d damn well better knock it off.

—Snarky as it is, though, it’s the kernel that proves Ponnuru’s basic argument: playing the preaching game won’t work for us, and it’s not because Americans are Bad, but because People are Cussedly Cantankerous. Besides, it’s letting them pick the battlefield and define the terms, and Ponnuru’s post is an avis most rara: advice from the other side that’s worth the taking. He just showed us where and when their flank will ambush us. Don’t let’s take the bait.

That said, I can’t get Nick Confessore’s crazy idea out of my head. Maybe providing health insurance through the Democratic party is in itself not so great a plan, no. But the idea of using what power we have to do what we can to weld together a reality-based safety net, doing what it can to end-run those most useful bits of the government currently headed for Grover Norquist’s bathtub, providing an alternative to the faith-based megachurch charity network, and thereby reconnecting the party with the people, and reminding the people directly just why it is we come together to get things done in the first place—

Sure, it’s buying votes with bread—a practice connected to traditions as old as the idea of a republic itself. It’s also one hell of a lot more useful than half-heartedly taking up tut-tutting about Grand Theft Auto.

One thing after another.

I do write about comics occasionally. —Over at Mercury Studios, Steve Lieber interviews himself with a list of “What’s it like to be a guy in the comics industry?” questions proposed by Devin Grayson, who’s maybe a little—tired?—of distaff curiosity. Dylan Meconis, meanwhile, having chewed what she bit off, teams up with Hope Larson for a lovely little online mini. And y’all are reading the Graphic Novel Review, right? Jenn did this month’s cover, since she’s between chapters on Dicebox—her shoes being ably filled with a charming little aside called “Sprouts,” by Kris Dresen. If you aren’t a subscriber yet, go, read it now: the first pages will be free till tomorrow morning, when the next pages upload.

Yeah, yeah. Sometimes I write about comics. Sometimes I just link a bunch of stuff.

Panem et circenses.

Still want to cut the red states loose and go your own urbane way? Well, hell. You don’t just have Mike Thompson on your side: a big hand, ladies and gentlemen, for the rhetorical stylings of Jim McNeil!

The states Kerry won, due solely to votes in just one or two cities each, are California, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington and Wisconsin. The cities that out-voted the rest of their state or adjacent areas are the District of Columbia, New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Portland and Seattle.

Kerry won just eight states (Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont) with balanced votes, and only two of these (Delaware and Hawaii) are outside of New England. These states gave him just 41 electoral votes.

The 11 cities listed above gave him 208 such votes, against wishes shown elsewhere statewide. Four more states could have had similar results due to city voting in Cleveland, Denver, St. Louis or the Miami to Palm Beach- area. Add D.C.’s three electoral votes and just 15 cities can award 278 electoral votes.

Thus, cities can pick our president, against the wishes expressed elsewhere nationwide.

Laugh if you like at his apparent misunderstanding of the whole point of democracy—that’s actually a standard tactic over in non-reality-based circles, where the vote is calculated by interest group, weighing the franchise of those you agree with more heavily, while discounting that of those you would consign to the Joy Division. Usually, though, this is reserved for the votes of those with funny skin: without the black vote, we’re told, over and over again, those Democrats would be sunk, yessiree. McNeil’s only innovation is to take the urban of “urban comedy” literally.

Now, I’m hardly the first person to have noticed it, but still: doesn’t one-state-two-state-red-state-blue-state make you think of the chariot races?

Factions were identified by their colors: either Blue or Green, Red or White. Domitian added gold and purple but they, like the emperor, were never popular and short-lived. Colors first are recorded in the 70s BC [sic]; during the Republic, when Pliny the Elder relates that, at the funeral of a charioteer for the Reds, a distraught supporter threw himself on the pyre in despair, a sacrifice that was dismissed by the Whites as no more than the act of someone overcome by the fumes of burning incense. According to Tertullian, these were the first two factions and, although the Blues and Greens are assumed to have appeared later in the first century AD [sic], it is likely that all four colors extend back to the Republic. Whatever their origin, by the end of the third century AD [sic], Blue and Green had come to dominate the other two factions, which seem to have aligned themselves as Red and Green, White and Blue.

A pairing of Green and White, at least, can be seen from lead “curse tablets” that invoke the most terrible fate for rival factions.

I adjure you, demon whoever you are, and I demand of you from this hour, from this day, from this moment, that you torture and kill the horses of the Greens and Whites and that you kill in a crash their drivers…

I conjure you up, holy beings and holy names, join in aiding this spell, and bind, enchant, thwart, strike, overturn, conspire against, destroy, kill, break Eucherius, the charioteer, and all his horses tomorrow in the circus at Rome. May he not leave the barriers well; may he not be quick in contest; may he not outstrip anyone; may he not make the turns well; may he not win any prizes…

Which, if nothing else, tells us the two-party system has always hated and feared potential third-party interlopers more than their soi-disant rivals. (Okay, weak. But it also answers the riddle of what color libertarian states are given on the Akashic electoral map.)

But! What do we do about this state of affairs? That’s the operative question, isn’t it? —Well, luckily for y’all, they used to show The Tomorrow People on Nickelodeon, and I watched a lot of it when I was a kid:

Though if you look deeper into the kaleidoscope and see past the loud colours that are the obvious horror, sci-fi and comic book references (John losing his “super powers” when imprisoned) this is quite an interesting science fiction story about an alien race who, like cuckoos, lay their eggs in different nests. The nests being different planets and the eggs taking the shape of the dominant life-forms on each planet, in this case taking the human form. The problem being that the energy the eggs need to hatch and fly free from earth can only be generated by human anger. The aliens have the power to create anger in humans by painting pictures of different planets that have temperamental weather conditions, which somehow affect the aggression levels of human beings who come into contact with them, and also by creating badges of different colours (blue and green) so the wearer of a green badge will become violent towards the wearer of a blue badge (but only when the weather is bad on, let’s say…Rexel 4!) The Tomorrow People’s job is to convince scary and very creepy Bowiealike alien Robert (who has been living in a junk shop with someone he calls Grandad, but actually appears to be a character that has fallen out of The Goon Show), that they can generate the energy needed by everyone on earth going to sleep at the same time and dreaming violent dreams whilst Stephen and John re-route the dream energy to the hatching aliens using giant stun guns! As John himself says “It’s an idea!”

So, hey. Let’s get cracking.

Looking for Mr. Finch.

Sometimes you wish they’d go for the pith, you know?

Of all the loathsome spectacles we’ve endured since November 2—the vampire-like gloating of CNN commentator Robert Novak, Bush embracing his “mandate”—none are more repulsive than that of Democrats conceding the “moral values” edge to the party that brought us Abu Ghraib.

That really ought to be shouted from battlements, for fuck’s sake, but—and much as I love em-dashes, and the clauses you can tuck inside ’em—there’s no rhythm. No rough music. No beat to pump a fist to.

Still. It’s one fuck of a clarion call.

Fred Clark gets it, too; and if his last line is more stiletto-snark than trumpet blare, well, the stiletto’s the weapon of choice right now in the op-ed alleys of the world.

Some political observers have responded to the electoral map and the exit polls by suggesting that if Democrats want to succeed in the scarlet states they will need to: A) accept the gelded notion of “morality” as a category primarily concerned with the condemnation of sexual minorities; and B) join in and embrace this impious form of piety to win more votes.

This is bad advice. It is also—what’s the word I’m looking for?—immoral.

We don’t need their morals. We have a better grasp of the morals they claim than they do. We don’t need their mandate. You ask Americans wherever they live what they want, what they really want from the world, you get them down to brass tacks and away from buzzwords slippery with rhetorical snakeoil, you do that and we win on the issues every single fucking time. What we need is their mantle, the one they drape over themselves before stepping up to the pulpit, the mantle that we let them steal because in a moment of weakness we felt sorry for the people they claimed to be. It’s that air of authority, that choice box seat in the frame they build themselves; it’s the high ground on the battlefield of their choosing, not ours. —It’s an old, old story, this theft, and it hinges on a fundamental human weakness: the confusion of style for substance, medium for message, dazzle for insight, mantle for morals—the design flaw lurking in our fantastic abilities to recognize patterns and leap to conclusions. It doesn’t matter that the emperor has no clothes, so long as he he’s got the mantle. It doesn’t matter, the words coming out of his mouth; we’ll help them along, after the fact, to what we think they were supposed to mean, until they’re no longer recognizable as what was said. We expect them to be moral, because authoritative, older men are always moral authorities—and so they are, no matter what nonsense they spew. We expect them to equivocate, because thoughtful, nuanced folk always equivocate, and would you look at that? —That’s what the mantle does, and that’s why we’ve got to get it back.

How? I don’t know. (Dismantle the hierarchies implicit in your language! cries a wag in the back. Well, bucko: that’s a strategy. What we need, here and now, are tactics.) —The mantle’s a slippery thing, too slippery to grab: it’s an air, yes, an attitude, but it’s also an expectation. It’s a way of seeing, but more imporantly, of being seen. It’s granted as much as it’s assumed; it’s taken as read, as much as it’s spoken. It’s a story, is what it is: the story we expect to see, and the roles we expect the people we’re seeing to play in it. Change the story, and you change the world. We don’t need to take back the mantle before we can go on to win; we take back the mantle, and we’ve won.

—Which puts us in the realm of strategy again. Not tactics. And anyway, sure as dishes and laundry, there’ll be another to fight in the morning.

But are you starting to see the problem with letting the red states go hang, with cutting our shining cities adrift on our blue hills and leaving them to their hardscrabble ignorance? That’s taking on the roles they deign to give us in the story they want to tell, the one they’ve been telling ever since they snatched the mantle from us—and while pretending “they’re” the conscious authors of this story is as artificial as pretending there’s only one story, or heck, that there’s a monolithic “them” against a unified “us,” and you can even make the argument that there’s a dark power in taking up the roles they give us and twirling our mustachios to the hilt, jiu-jitsuing their story over its logical cliff, still: the mills of poetic justice grind even slower than the other exceeding kind, and anyway, there’s other ways.

What other ways?

(What was I saying about pith?)

Look, this whole thing got started because somebody was searching for arthurian parallels and washed up here and when I went poking to remind myself what Arthurian parallels had to do with what I’d thought I’d written, and I found myself in the middle of some stuff about a Joss Whedon television show that has been squatting, all unseen, at the heart of this one-state-two-state-red-state-blue-state bullshit because the story that’s being told, the story that we’re telling, the story that we’re letting them tell has no place for it. And this is pop culture, yes, this is art, such as it is, and all of that is chopping wood and carrying water when what we need, here and now, are tactical airstrikes (our best targets being the news, and how we get it, and how we pass it along: the stories we make all unknowing when we do, and how we go about changing them: that word, sir, “morals”: I do not think it means what you think it means), but this is a long, slow, tedious business, writing, and grace comes from unexpected quarters, and fortune favors the prepared, and this is what I’ve got, here and now. Make of it what you will. Wood’s still gotta get chopped; the water won’t carry itself, and as far afield as we might have wandered from Abu Ghraib and economic injustice, still: the pulpiest attack on this poisonous story we’ve somehow been tricked into telling, the most half-assed all-unknowing attempt at snatching the mantle from the emperor’s bare shoulders—it’s infinitely more useful than yet another round of fucking the South.

And Whedon’s a step or two up from pulp.

Whedon has cited in a number of interviews the effect his professor Richard Slotkin had on him at Wesleyan, and Slotkin’s book, Regeneration Through Violence. With Firefly, I think he was starting to play directly with those ideas in an edgily dicey manner. —Set 500 years in the future, the show’s political setting was a none-too-subtle recreation of our own post-Civil War Reconstruction: the Alliance of rich, industrialized central or core worlds had fought a war to quell the rebellious, rural, economically disadvantaged outer planets. The rebel “brown coats” had been put down, the frontier overwhelmed, the Union cemented, and now all our heroes can do is scrape by from job to job, keeping a low profile. It’s a standard western setting, troped up into the future, yes—but that doesn’t account for the chill that went down my spine when, in the (second) pilot, as our heroes engineer their last-minute getaway, Mal (the captain of the ship, a former rebel who still defiantly wears his brown coat), smiles and tosses a bon mot at the villains of the set-piece: “Oh,” he says, “we will rise again.”

Jesus, I thought. Does Whedon know what he’s playing with here?

After all, playing by the rules of the metaphor, Mal maps onto the Confederacy—the rebellious, rural, economically disadvantaged butternut-coats that lost. And he’s stubborn, proud, independent, self-reliant, a rugged, gun-totin’ he-man, whose moral gut regularly outvotes the niceties of his ethics, and who nicely fills out a tight pair of pants. He is, in many ways, the sort of ideal idolized by reactionaries and conservatives, and his beloved brown-coat rebellion was everything the neo-Confederates claim of the poor, put-upon, honorable South.

“Oh,” he says. “We will rise again.”

But! Mal was also rather explicitly something of an antihero. Whedon calls his politics “reactionary”—oh, heck, at the risk of derailing my sputtering argument, let me quote him at length:

Mal’s politics are very reactionary and “Big government is bad” and “Don’t interfere with my life.” And sometimes he’s wrong—because sometimes the Alliance is America, this beautiful shining light of democracy. But sometimes the Alliance is America in Vietnam: we have a lot of petty politics, we are way out of our league and we have no right to control these people. And yet! Sometimes the Alliance is America in Nazi Germany. And Mal can’t see that, because he was a Vietnamese.

And there’s the world Mal and his crew and fellow travelers play in, where the folksy talk is peppered with Cantonese slang. Women work as mechanics and fight in wars. The frontier isn’t romantic; it’s hardscrabble, nasty and brutal. The Alliance isn’t Evil, just banal, mostly—and what conflict and oppression we see is driven not by race or religion or (admittedly homogenized) ethnicity, but class and economics, pure and simple.

Whatever it is that’s going to rise again, it sure as hell doesn’t look like the neo-Confederate dreams of the South.

The last batch of westerns—Peckinpah, Leone, et al (and yes, I know morally ambiguous began with John Ford, at least; let’s keep this simple)—rather famously took the straight-shooting archetype of the morally upright western hero: the cowboy, the marshal—and turned his independence and integrity and self-reliance rather firmly inside-out. And that was a good and even necessary thing to do, and anyway it made some kick-ass movies. But in savaging the happy macho myths America had told itself back in the 1950s, in trying to cut away the swaggering pride and racism and cocksure aggrandizement that landed us in Vietnam, among other things, we went too far. Hokey as it might seem, there was a baby in that bathwater. And what I think Whedon was doing with his SF western was very deliberately walking up to the other side of the kulturkampf and taking their idea of a good man—the independence, the self-reliance, the folksy charm, the integrity (cited more in breach than practice by the Other Side, whose idea of self-reliance means I got mine, screw you—but I grow partisan, I digress)—he was taking that idea of a good person, a person capable of doing good things, and giving it back to us.

Of course, what you have to realize there, is the story he was trying to change is one we tell ourselves. (Which is why Mal’s an atheist, see. This is therapy, not outreach.) —Thing about changing stories is everything’s up for grabs until the new narrative settles in, and nobody’s gonna know exactly how everything falls out until it does—and that’s maybe another reason why it’s comfortable to paint ourselves with blue-state woad and charge their rhetorical guns, yet again. At least we know what to expect, right?

There’s other ways, though. Might behoove us to start looking for them.

Watchmaker, watchmaker, make me a watch.

Whenever I hear about something like, oh, how close we’re maybe getting to reconciling general relativity with quantum theory, I think of the termites.

The termites: there’s this guy on the TV, one of those professionally unflappable British narrator guys, crouching three feet underground in a cramped little dig somewhere in the middle of the East African desert, playing his headlamp over a nightmarishly inscrutable labyrinth of twisty little passages, all alike, maybe wide enough to cram a finger into. The labyrinth is mirrored in the ceiling inches over his stooped shoulders. He’s inside the base of a termite mound, this narrator guy, in an heroically excavated cross-section. Outside, above, it’s a weird flat sail, razor-thin at the top, seven to ten feet tall and it’s easily that long. Aligned north to south so it catches the full weight of the morning and evening sun, but hides in its own sort-of shadow from the brutal noonlight. Inside, those labyrinthine fissures snake through the sail, hollowing it out like worm-eaten driftwood, sinking down another yard or so below the narrator guy’s feet, down to where the mud starts, kept cool and damp by seepage from the water table.

And all of it done by termites: hordes and hordes of plump pale bugs as big as the first two joints of your index finger, that hoisted the sail, dug the labyrinth, and now swarm blindly about, sealing one passage here, opening another there. Why? says the narrator guy, three feet underground. Why this incredible effort, this marvel of insect engineering? His unflappable mien not at all compromised by the dirt streaking his cheeks. Air conditioning, says the narrator guy. The difference in temperatures between the cool air underground and the air in the sail, heated by the sun, sets up a constant flow throughout the nest. Regulated by those swarms of tiny HVAC techs, opening this shaft, closing the other, the ambient temperature throughout most of the nest never fluctuates outside of a narrow 2º Fahrenheit window. And a good thing, that, says the narrator guy. There’s a fungus the termites depend on for their digestion which can only flourish in that temperature range. Without the termites and their marvel of insect engineering, the fungus would wither up and blow away in the 120º afternoons. And without the fungus: no termites.

Hearing this made me all shivery inside. Here I am, a rakishly secular humanist with just enough science to get me into trouble, and this unflappable narrator guy is breezing past an incredible marvel of inhuman ingenuity with a dry, unflapped chuckle, heading off after the next incredible marvel—weaver birds, maybe, or octopi that open Mason jars with their tentacles. I can’t remember. I was left behind with a startling sign of intelligent design, one far more impressive than that dam’ bombardier beetle, and nothing but a dull piece of logic to pick it apart with. How on earth could trial and error, self-organization, and evolutionary pressures have produced such an intricate system of vents and a thermostat far more effective than the one in my office? How could it all have had enough time to work itself out to support this fungus, when without it, the fungus would die? When without the fungus, the termites would starve?

Could it all have been made, and not just happened?

Luckily, I have a friend who’s able to help me sharpen my logic and show me which end to hold it by. (Thanks, Charles.) —My mistake, there on the couch, gobsmacked by the unflappable narrator guy, was (rather foolishly) to assume the fungus’s dependence on that precisely narrow temperature window, and the termites utter dependence on the fungus, were constants throughout the history of their symbiosis; not so. The fungus was hardier in the past; the termites less finicky. The incredible success of their relationship was finely tuned over an incredibly long stretch of time—evolved, one might say, along with the termites’ instincts for building with spittle and homeostasis, and the fungus’s for, well, whatever it is fungi do all day—until it reached its current interdependent apex, littering the East African desert with monuments seven to ten feet high.

So it’s a little thing, and a bone-headed error, and I’m not at all suggesting it’s the same thing, no—well, maybe similar, perhaps, in kind if not degree, but still: I think about that shiver I felt, looking at the inscrutable labyrinth; I remember the ghostly whisper in the back of my brain, insisting despite all I know that it must have been made and couldn’t just have happened, and I think, I think I know what it is that makes people take up ideas like the anthropic principle. And maybe it’s because I share that feeling that I take such an immediate and visceral dislike to them. (Well. The ideas. I mean, it’s nothing personal.)

Nails.

Fuck the South? —I’m a ’Bama boy in something of a self-imposed exile, a Yankee throwback who still has strong opinions on grits, and I like a good rant as much as the next raconteur, but you know what? Fuck you. No, seriously: fuck you. There’s more than enough stars and bars to go around. Sure, that asshole wrote that thing where he cut off his nose to spite his face, but so what? Assholes like that have been writing masturbatory fantasies about strange fruit for years. There’s hardball, but there’s also letting them set the rules and pick the battlefield, and it doesn’t take a Sun Tzu to point out what a mug’s game that is.

Kos tells us Frank Rich nailed it—as yet another Canute spitting into the incoming CW tide about those pesky “values voters,” anyway. And Rich has his point, even if it’s thin and dispiriting. —But when I want some quality spleen-vent, I tap the source, and once more the pseudonymous skimble fails to disappoint:

As a Blue Stater, I am sick of being told how negative I am and that I hate Christians, or the American South, or heartland states, or gun owners, or people less educated than me, or families, or rural culture.

I don’t hate any of that.

I hate incompetence. I hate unchecked greed. I hate secrecy in public institutions. I hate discrimination. I hate the distortion of public discourse by giving common words coded meanings. I hate coercion. I hate disproportionality in prosecution and sentencing. I hate the theft of public property for private gain. I hate having my privacy violated, especially in medical and financial matters. I hate that members of this administration avoided military service but abuse veterans and send soldiers and reservists to their deaths—and still pretend to recognize Veterans Day.

All of these things reduce the choices available to our citizens. All of these things contradict compassion. All of these things reduce freedom. The bullshit versions of compassion and freedom exclude the real things from our lives.

That’s what I hate.

Added bonus.

While cruising some Goats-related sites on the internet for the bit prior, I stumbled across as neat a piece of writing advice as you could ask for, tossed off the cuff of an engaging interview. So, ladies and gentlemen, the Mountain Goat himself, John Darnielle:

The problem with most people that write that way is that they focus more on “is it true?” than “is it good writing?” Most things don’t resonate when they’re true; it’s how the audience hears it when it doesn’t have anything to do with them. So I’ve always been resistant towards that, from since I was a kid and wanted to become a writer. They’d say, write about what you know, and I’d say I’m a fucking kid! [laughs] I don’t know anything—I wanna write about monsters! But at the same time, I think my new songs are so much better than the old songs, and they’re more rooted in truth. I guess what I’m going at is, first learn to write, then try to write about yourself, once you’re able to distance yourself, to lose the notion that what was so spectacular to you isn’t necessarily so spectacular to everyone.