Fake news.

So I had this whole riff on how the controversy (?) over how it turns out James Corden’s Range Rover is being towed whenever they film those Carpool Karaokes (!), on how that’s what happens when the news is filled with Republicans pissing on your leg and telling you it’s raining people telling violently bald-faced lies without even caring whether they’re believed, and it’s overwhelming everything that you and everyone you know and love knows to be true, and there’s nothing you can do about it, you can’t call those people out, you can’t touch them, you can’t even spit in their coffee, and changing the channel does no good at all anymore, it’s in the air, it’s on your phone, it covers you now like some sort of film, in your hair, your face, like a glaze, a coating, a patina of shit, I mean, and voting doesn’t do any God damn good, and even if you are a Republican openly affect to agree with them this constant grinding degrading cognitive dissonance is going to take a toll, is going to build up pressure that has to be relieved somewhere, somehow (to get hydraulic for a moment), is going to squirt out at the oddest moment, lashing when it sees a chance to feel weirdly betrayed by a cheaply obvious bit of televisual trickery, I mean, who out there is really all that invested in the belief that actors must really be driving when they’re playing at driving a car? (James Garner as always excepted, of course.) —I had this whole riff, but it turns out it’s really just that James Corden’s actually kinda a dick, and people don’t like him. So.

Punk’d.

All of these strategies can produce terrific stories. But none seems capable of generating the sort of excitement cyberpunk once did, and none has done much better than cyberpunk at the job of imagining genuinely different human futures. We are still, in many ways, living in the world Reagan and Thatcher built—a neoliberal world of growing precarity, corporate dominance, divestment from the welfare state, and social atomization. In this sort of world, the reliance on narratives that feature hacker protagonists charged with solving insurmountable problems individually can seem all too familiar. In the absence of any sense of collective action, absent the understanding that history isn’t made by individuals but by social movements and groups working in tandem, it’s easy to see why some writers, editors, and critics have failed to think very far beyond the horizon cyberpunk helped define. If the best you can do is worm your way through gleaming arcologies you played little part in building—if your answer to dystopia is to develop some new anti-authoritarian style, attitude, or ethos—you might as well give up the game, don your mirrorshades, and admit you’re still doing cyberpunk (close to four decades later).

It was not one or two or a mere scattering of women, after all, who participated in women’s renaissance in science fiction. It was a great BUNCH of women: too many to discourage or ignore individually, too good to pretend to be flukes. In fact, their work was so pervasive, so obvious, so influential, and they won so many of the major awards, that their work demands to be considered centrally as one looks back on the late ’70s and early ’80s. They broadened the scope of SF exploration from mere technology to include personal and social themes as well. Their work and their (our) concerns are of central importance to any remembered history or critique. Ah ha, I thought, how could they suppress THAT?!

This is how:

In the preface to Burning Chrome, Bruce Sterling rhapsodizes about the quality and promise of the new wave of SF writers, the so-called “cyberpunks” of the late 1980s, and then compares their work to that of the preceding decade:

“The sad truth of the matter is that SF has not been much fun of late. All forms of pop culture go through the doldrums: they catch cold when society sneezes. If SF in the late Seventies was confused, self-involved, and stale, it was scarcely a cause for wonder.”

With a touch of the keys on his word processor, Sterling dumps a decade of SF writing out of cultural memory: the whole decade was boring, symptomatic of a sick culture, not worth writing about. Now, at last, he says, we’re on to the right stuff again.

Is something broken in our SF? Oh dear God and all those little fishes, yes, of course, indeed—but it goes so very terribly much further than the horrid enclitic. SF, as such, requires a novum new and big and strong enough to estrange us all to a cognitive breakthrough—and oh, God, the power required to effect the change we need now is so great—the responsibility demanded—we couldn’t—we couldn’t possibly—

Unfinished Business.

“Rather than rehearsing nineteenth-century reform as a history of bourgeois abolitionists having tea and organizing anti-slavery bazaars for their friends, Jackson offers electrifying accounts of Boston freedom fighters locking down courthouses and brawling with the police. We learn of preachers concealing guns in crates of Bibles and sending them off to abolitionists battling the expansion of slavery in the Midwest. We glimpse nominally free black communities forming secret mutual aid networks and arming themselves in preparation for a coming confrontation with the state. And we find that antebellum activists were also free lovers who experimented with unconventional and queer relationships while fighting against the institution of marriage and gendered subjugation. Traversing the nineteenth-century history of countless ‘strikes, raids, rallies, boycotts, secret councils, [and] hidden weapons,’ American Radicals is a study of highly organized attempts to bring down a racist, heteropatriarchal settler state—and of winning, for a time.” —Britt Rusert

Disposable.

Before (the picture upon being taken):

After (the picture upon being published):

There was no ill intent. AP routinely publishes photos as they come in and when we received additional images from the field, we updated the story. AP has published a number of images of Vanessa Nakate.

Subsequently (the picture anent the explanation):

We regret publishing a photo this morning that cropped out Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate, the only person of color in the photo. As a news organization, we care deeply about accurately representing the world that we cover. We train our journalists to be sensitive to issues of inclusion and omission. We have spoken internally with our journalists and we will learn from this error in judgment.

The subsequent more-of-an apology:

Vanessa, on behalf of the AP, I want to say how sorry I am that we cropped that photo and removed you from it. It was a mistake that we realize silenced your voice, and we apologize. We will all work hard to learn from this. Sincerely, Sally Buzbee

— Sally Buzbee (@SallyBuzbee) January 26, 2020

David Ake, the AP’s director of photography, told Buzzfeed UK that, under tight deadline, the photographer “cropped it purely on composition grounds.”

“He thought the building in the background was distracting,” Ake said.

Free as in just fuckin around.

“None of this free time just arises like water from an artesian well. Even though we all live in the stream of time, which flows toward us until we die, much of what is ironically called ‘our’ time is doled out in advance: working to live, to service debt, to keep our own houses in order. Any free hour rests in an intricate web of other people’s work: those who are keeping you fed, warm, sheltered, those who raised you or are raising your offspring, those who are picking up the garbage today or checking in on your aging parent or making sure the roads are patched and the subways are running. Free time is about as spontaneous and random as a cherry tree in Central Park. It is also just as gorgeous, and within it we can be as spontaneous and random as if we were just splashing through time’s current. It is both the homeland of individuality and the crowning collective achievement.” —Jedediah Britton-Purdy

reformacons, blood-and-soilers, curious liberal nationalists, “Austrians,” repentant neocons, evangelical Christians, corporate raiders, cattle ranchers, Silicon Valley dissidents, Buckleyites, Straussians, Orthodox Jews, Catholics, Mormons, Tories—

“It did all raise a question. What if Trump had dialed down the white nationalism after taking the White House and, instead of betraying nearly every word of his campaign rhetoric of economic populism, had ruthlessly enacted populist policies, passing gargantuan infrastructure bills, shredding NAFTA instead of remodeling it, giving a tax cut to the lower middle class instead of the rich, and conspiring to raise the wages of American workers? It doesn’t take much to imagine how that would play against a Democratic challenger with McKINSEY or HARVARD LAW SCHOOL imprinted on his or her forehead. There seemed to be two futures for Trumpism as a distinctive strain of populism: one in which the last reserves of white identity politics were mined until the cave collapsed and one in which the coalition was expanded to include working Americans, enlisting blacks and Hispanics and Asians in the cause of conquering the condescending citadels of Wokistan. Was it predestined that Trump would choose the former? Steve Bannon was already audience-testing Trumpism 2.0, wrong-footing the crowd at the Oxford Union with complaints about the lack of black technicians in Silicon Valley. Why couldn’t Trumpism go in this direction in reality? The shrewdest move for the NatCons would surely have been to attract as many non-whites as possible to the Ritz and strike fear into the hearts of the globalists with a multiracial populist carnival—a new post-Trump pan-ethnic coalition that would someday consider it quaint that it had once needed to begin conferences with the profession: We are not actually racist.” —Thomas Meaney

A better solution to the problem.

“Firefighters’ calendar featuring Portland homeless camps” is one hell of a 2020 mood.

Fire officials haven’t identified the firefighter who made the calendar. It surfaced at Portland Fire Station No. 7, one of the city’s busiest stations in the Mill Park neighborhood at 1500 SE 122nd Ave., and firefighters from other stations apparently expressed interest in having one of their own, according to Fire Bureau members. Twenty-four firefighters are assigned to Station 7.

It case it’s not clear from the jump, the calendar wasn’t laudatory.

Alan Ferschweiler, president of the Portland Fire Fighters Association, said the calendar, while insensitive, highlights greater problems that aren’t getting enough attention from city leaders: “the friction between firefighters and the houseless population” and an “overstressed work force.”

Firefighters, he said, usually are sent to deal with low-level medical calls at homeless camps or to put out fires at the camps. Because Portland police aren’t responding as often to these calls, firefighters often feel unsafe or face aggression from people who are abusing drugs or alcohol, Ferschweiler said.

“Those negative interactions have a resounding effect on our members,” he said. “Police have responded less and less and less to those calls with us. That’s part of the situation too. I feel there’s calls where I wish the cops were here.”

Of course, there are very good reasons to keep interactions between the Portland Police Bureau and the houseless population at a minimum.

And one might be thankful it’s paramedics showing up for medical emergencies, and firefighters for fires, and not armed police, and one may lament that our first responders must so often respond firstly to situations and circumstances for which there is no clear-cut training, with resolutions far beyond the immediate scope of their admirably focused powers, but one can also take note of the curious rhetorical figure in Ferschweiler’s statement, “the friction between firefighters and the houseless population,” which whisks us with breathtaking suddenness to some notional arena where two unitary sets of stakeholders, firefighters and the houseless population, might set their competing agendas to duking it out with, sadly, some little friction.

—It’s understandable, to be charitable, that one would be so despondent at the abjunct between what one is tasked with doing or even what one can do at all, and what must needs be done, that one turns one’s efforts to what one can reach, metonymically speaking; thus does fighting homelessness become fighting the houseless population, much as what happened with the war on drugs. —And one could be so horrified by the idea of one’s own precarity that one might choose to assert one’s security by insisting such horrors happen only to a certain certain sort, you know, the houseless population, those people, THEM—look, there they are now, over there, not me, nope, nossir! —But such seductive turns of thought however understandable turn in your hand, lead you astray, make you think you’ve grabbed hold of something that isn’t there at all:

“Let’s have some talk about the problem we’re having,” he said.

A stranger’s stabbing Saturday night of an off-duty fire lieutenant who was at a Portland bar celebrating his wedding anniversary further highlights the problem, the union president said.

And surely we all can agree no matter how figurative our rhetoric that to see this incident as a skirmish in the “friction” between firefighters and the houseless population (McClendon, the estranged “stranger” who stabbed above, has no fixed address)—that would be dizzyingly unhinged. Yet here we are, at the end of our discussion, wrapping it up with this, as if it says anything at all about a Fire & Rescue station, frustrated by friction, letting off steam through the “dark humor” of a calendar that mocks homeless camps.

“We want to have a better solution to the problem,” Ferschweiler said. “We want people like Paul to be able to come downtown, have a good time with his wife and be able to go home safely.”

The borders of US and THEM, downtown and safety, are easy enough to sketch with a map like that. —Myself, I want people like Debbie Ann Beaver to be able to take the medicine they need in peace. This friction kills.

Painstakingly æstheticized chisme.

“After a few days,” says Myriam Gurba, “an editor responded. She wrote that though my takedown of American Dirt was ‘spectacular,’ I lacked the fame to pen something so ‘negative’.” Let’s make sure she has fame enough to pen as negative as she wants in the future. —Some additional background on Oprah’s latest bookclub pick. Remember, kids: the fail condition of condemnation is reification!

Quinnipiac in retrograde.

“But received wisdom about electability is powerful precisely because it defies reason and is resistant to critical scrutiny. Like many of the other concepts that shape electoral punditry and political discourse—charisma, qualification, momentum, authenticity—electability is a shibboleth of a political mysticism that ‘tickles the brain’ only because it cannot fully engage it—a drab, gray astrology, maintained by over-caffeinated men.” —Osita Nwanevu

“—I pray you, as I pronounced it to you, trippingly—”

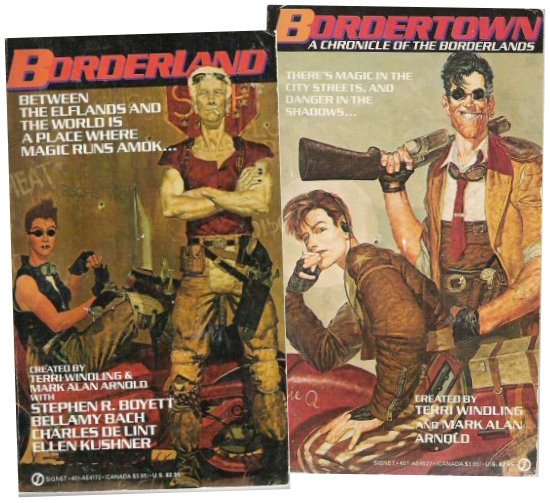

While I was poking about, looking for what I’d said back in the day about ostranenie and the unheimlich (mostly I was trying to remember that push-me-pull-you refrain, oh I see, oh I get it, which I didn’t end up using, but make what you will of the fact I forgot), anyway, I ended up over at the Mumpsimus, contemporaneously, and saw a link in a linkdump that said, “Elves killed by punk rock,” and of course I clicked on it. —Wouldn’t you?

Magic—or more precisely, the “magical”—was one of the first casualties of punk rock. As guitar solos contracted and song structures were shaved to a stump, with amazing speed we lost our dragons, our druids, our talking trees—the whole seeping, twittering realm of the fantastic was suddenly banished, as if by a lobotomy. It survived, lurkingly, in the lower realms of heavy metal and Goth, but no one would ever again fill a stadium by singing about Gollum, the evil one. Punk rock had killed the elves.

And, well, I mean, you know what I’m gonna say about that.

Magic will not be contained. Magic breaks free. It expands to new territories, and it crashes through, barriers, painfully, maybe even dangerously, but, ah, well. There it is. Magic, uh, finds a way.

—And we can quibble about category errors and gestures and deeds and what does or doesn’t count as punk rock to a high school kid in 1987, casting about for whatever wonder-generating mechanisms are in reach, and maybe it’s less punk and more sludge, I don’t know, you can head over to YouTube to listen to the subjects of this fifteen-year-old review for yourself, but mostly the reason I’m mentioning this at all is something from the end of it, said by Dead Meadow’s singer and guitarist, Jason Simon. “These writers,” he says, “to me—”

(—he’s talking about the writers that the writer says he said are his favorites, and these writers of course are folks like H.P. Lovecraft, Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, and Arthur Machen—)

These writers, to me, are just a celebration of pure imagination. And it seems like the imagination is suffering these days—so many images coming at you, so shallow and so fast. We’re trying to create songs with some space in them, some imaginative space, to give people some room.

It’s an importantly counterintuitive point, about how the imagination suffers under the onslaught of imagination, and how absolutely vital it is to give the audience some credit.

Tripping the light.

“The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams,” says the man, and, okay? I guess? I mean, I dream in English, and I’d bet he does, too, mostly, but I don’t think he means the best fantasy is written in English, I think he means the best fantasy is written in the language you grew up with, that you know in your bones, because that’s where the tricks work best: your feet think they know the stones of this path, and follow them without thinking; a clever gardener can then lay them to lead them all-unaware through shadowy copses by undrunk brooks to sudden breathtaking impossible vistas that couldn’t, shouldn’t be where they seem—and yet—

All the farm was shining with the hideous unknown blend of colour; trees, buildings, and even such grass and herbage as had not been wholly changed to lethal grey brittleness. The boughs were all straining skyward, tipped with tongues of foul flame, and lambent tricklings of the same monstrous fire were creeping about the ridgepoles of the house, barn, and sheds. It was a scene from a vision of Fuseli, and over all the rest reigned that riot of luminous amorphousness, that alien and undimensioned rainbow of cryptic poison from the well—seething, feeling, lapping, reaching, scintillating, straining, and malignly bubbling in its cosmic and unrecognisable chromaticism.

William Dean Howells wrote ten horror stories between 1902 and 1907. The stories are not highly regarded by most critics of horror; a typical comment is S.T. Joshi’s sneer that “the element of terror, or even the supernatural, in these stories, is so attenuated… that the overall effect is a kind of pale-pink weirdness entirely in keeping with the era in which they were written.”

We read fantasy to find the colors again, I think.

“The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams,” he tells us, but it turns out he’s more concerned with imminence, and evanescence, something “more real than real” that only lasts for one “long magic moment before we wake.” —And, I mean, okay, I don’t know about you, but as for me, I barely remember my dreams; I wake up knowing I have dreamed, but mostly I’m left with a (yes) color, a tone, a vector or at least a sense of motion, scraps that dissolve even as I try to pin them down, and there’s something in that grasping-after, that sense of having lost what I never knew I’d had, that gets at something in fantasy, sure, but—

“Fantasy is silver and scarlet,” he says, “indigo and azure, obsidian veined with gold and lapis lazuli,” and here I’m brought up short—is that it? Why stop here? “Obsidian veined with gold,” I mean, you can find that in the bathroom of a Trump hotel. You mustn’t be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling:

She spoke, and the first low beams of the sun smote javelin-like through the eastern windows, and the freshness of morning breathed and shimmered in that lofty chamber, chasing the blue and dusky shades of departed night to the corners and recesses, and to the rafters of the vaulted roof. Surely no potentate of earth, not Crœsus, not the great King, not Minos in his royal palace in Crete, not all the Pharaohs, not Queen Semiramis, nor all the Kings of Babylon and Nineveh had ever a throne room to compare in glory with that high presence chamber of the lords of Demonland. Its walls and pillars were of snow-white marble, every vein whereof was set with small gems: rubies, corals, garnets, and pink topaz. Seven pillars on either side bore up the shadowy vault of the roof; the roof-tree and the beams were of gold, curiously carved, the roof itself of mother-of-pearl. A side aisle ran behind each row of pillars, and seven paintings on the western side faced seven spacious windows on the east. At the end of the hall upon a dais stood three high seats, the arms of each composed of two hippogriffs wrought in gold, with wings spread, and the legs of the seats the legs of the hippogriffs; but the body of each high seat was a single jewel of monstrous size: the left-hand seat a black opal, asparkle with steel-blue fire, the next a fire-opal, as it were a burning coal, the third seat an alexandrite, purple like wine by night but deep sea-green by day. Ten more pillars stood in semicircle behind the high seats, bearing up above them and the dais a canopy of gold. The benches that ran from end to end of the lofty chamber were of cedar, inlaid with coral and ivory, and so were the tables that stood before the benches. The floor of the chamber was tessellated, of marble and green tourmaline, and on every square of tourmaline was carven the image of a fish: as the dolphin, the conger, the cat-fish, the salmon, the tunny, the squid, and other wonders of the deep. Hangings of tapestry were behind the high seats, worked with flowers, snake’s-head, snapdragon, dragon-mouth, and their kind; and on the dado below the windows were sculptures of birds and beasts and creeping things.

“Fantasy tastes of habaneros and honey, cinnamon and cloves, rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer,” and now I can only sigh: we were talking again just a couple of weeks ago about how flavor’s the very essence of a sylph, and to mistake the flavor for its ingredients is one of those, whaddayacall ’em, category errors; to set “rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer” as our sylphs against the (by implication) drab reality of “beans and tofu” is to not only lose the vegetarians in the audience, or those who’d quail before a cellar full of nothing but sweet wine: it loses that astounding little plate of hiyayakko we had in that strip-mall sushi joint in North Carolina, just a chilly silky geometrically perfect cube of tofu topped with flakes of ginger and slivers of scallion and tendrils of bonito and oh, that one first perfect bite, and it loses what you can make with a bag of dried black beans and a couple of cloves of garlic and salt and pepper and a cup of plonk and some water and laughter and time. —It’s precisely the same error that tells us fantasy’s only to be found in Minas Tirith or Gormenghast or Camelot, and never in plywood or plastic or (yes) strip malls. It’s to mistake the gesture for the deed, confusing the things the wonder-generating mechanisms have been attached to with the wonder-generating mechanisms themselves—my God, if you can’t conjure with a name like “Burbank,” or “Cleveland,” you’ve no business being in this business. —Multi-million–dollar empires aside.

And I know, I know: this passage is flavor text from an album intended to be carted about at conventions, collecting autographs; it was written a quarter-century ago, long before Martin’s fantasy ate the world, or at least HBO; well before the fuck-you money, which maybe helps to explain why his images of fantasy are so luxurious, drawn from Harry & David and Conran, set against beans and rice. (Oh, but that’s uncharitable, coming from me with my Japanese appetizers and cellars of peppery wines and those tricksily landscaped gardens there, up at the top.) —It’s old, and it’s slight, this passage, it’s silly, sure, but it keeps coming back—

—and silly or slight or old as it is, one of the most important lessons fantasy has to teach us is that you are what you pretend to be. The gesture may not be the deed, but performing the gesture is itself a deed, and if you keep telling us fantasy’s written in the language of dreams, that it fulfills wishes, that it gives you the tastes you yearn for and the colors you want to find again, it’s gonna raise a lot of terribly pointed questions when the fantasy you’re most known for, the deed your gesture performs, the work you put into the world is so very full of white folks and rape. —There’s something else going on here, something more, and to paper it over with something so silly and so slight is to turn those words to ash with the slightest consideration.

(“They can keep their heaven,” he says; “When I die, I’d sooner go to Middle-earth,” and, I mean, I’ve been to the Shire? Like, actually been there? Drove out on a whim fourteen years ago, when our car was new. —Whole place went under just a bit later, in the Crash of ’08.)

“The triplex, sir, is a good tripping measure;”

I’m reading Neveryóna, which is not, I hasten to add, in any way, shape, fashion, or form, a sword-and-sorcery story; it isn’t even a fantasy—it’s wholly, cheerfully, entirely SF: it’s just that the novum that estranges us past a conceptual breakthrough into a topia isn’t so much cybernetics or ballistics, but the very act of reading (in its expansive, semantic screwdriver sense) and its turn in turn to writing—

(Yes, I know there are dragons in it. That doesn’t make it a fantasy. I mean, there are dragons in Stars in my Pocket like Grains of Sand, and you wouldn’t call Pocket a fantasy, now, would you?

(Actually… Now that I think about it…

(Oh, for God’s sake, the Nevèrÿon books are [mostly, somewhat] explicitly part of the Informal Remarks toward the Modular Calculus! Which include Trouble on Triton! Which is the largest moon of the planet Neptune! And they include the Harbin-Y lectures of Ashima Slade! Who died when the gravity was cut to the city of Lux, on Iapetus! The third largest moon of Saturn! It’s SF!)

—But I digress.

I’ve been (re)reading Neveryóna, and I’ve gotten to what I remember having been one of my more favorite bits (after the Tale of Old Venn, anyway, which is a tour-de-something-or-other), when the dragon-rider, Pryn (née pryn), a “loud brown fifteen-year-old with bushy hair,” is invited to the house (castle) (cavern) (palace) (compound) of the Earl Jue-Grutn, and begins to see (as we begin to see) how intimate and implacable is the power that rules this fantastic and philosophical empire. —The earl invites her to see his collection of different kinds of writing systems, which includes on a shelf on a wall a collection of painted statuettes—

“—three cows, followed by two women bent over three pots, followed by those pyramids stippled all over; I have it on authority they represent heaps of grain—”

“And those are trees there!” Pryn pointed. “Five, six… seven of them.”

“The same authority informed me that each tree should be read as an entire orchard. The barrels at the end are most likely lined with resinated wax and filled with beer, much like the brews you help Old Rorkar produce.”

To either side of this display is a picture in a frame. The one—

“—there to the right, is inked on a vegetable fiber unrolled from a species of swamp reed.”

Pryn looked more closely: simple strokes portrayed three four-legged animals. From the curves at their heads, clearly they were intended to be cattle—no doubt the same cows that the statuettes represented; for next to them were more marks most certainly indicating two schematic, sexless figures bending over three triangular blotches—the pots.

And the other:

Left of the sculptures, in the other frame some dry, brownish stuff was stretched. On it were blackened marks, edged with a nimbus that suggested burning. “What’s this?” Asking, she recognized the even clumsier markings as even more schematic animals, people, pots, trees, barrels, grain…

“The same authority assured me it was flesh once flayed from his own horridly scarred body—he was a successful traveling merchant when I knew him, which lent its own dubiously commercial reading to the three pieces he sold me. Myself, I’m more inclined to suppose it is the branded skin of some slave’s thigh, stripped from the living leg; all too often—five times? six times? seven?—I saw my father oversee the commission of such atrocities on the bodies of the criminals among our own blond, blue-eyed chattels. From even further north than you, that scarred black man had, no doubt, as many reasons for speaking truth as he had for lying. But consider all three—”

Yes, let’s. —Delany (the earl) (Pryn) (we) rather immediately ascribe the three as art (concerned with representation, yes, but also the exercise of craft required to wring that representation from the materials chosen, or available), as writing (smooth, dispassionate, a meaning apart from the context that gives it meaning), and as pure ideological imposition, as terror, as violation, as revelation, as (?) POWER; but then rather immediately moves past these simple descriptions to a (much) more interesting question: which came first?

“Which one of the three inspired, which one of the three contaminated, which one of the three first valorized the subsequent two in our cultural market of common conceptions?”

And those of you who’ve been paying attention over the years, or who noticed the title, or can count at least to three, you’re maybe already thinking you know where I’m going with this, the maid-mother-crone, the creator-sustainer-redeemer, the Cluthian Triskelion of fantastika, the model I’ve been borrowing, the argument of the thing-that-argues, the prick against which the sermon kicks—

“Again, the initial apprehension of beauty, in an entirely different way from the initial apprehension of disinterest, redeems both modes of later inhumanity it engenders on the grounds that they are, still, misreadings—one an underreading, one an overreading certainly, but nevertheless both misguided, because impoverished, because unappreciative of the mystical, beautiful, originary apprehension which a more generous reader can always reinscribe over what the misguided two chose to inflict in terms of pain or boredom.”

—but I’m not saying that Delany’s saying (Pryn is saying) (the earl is saying) that one of these things is fantasy, and one SF, and one is horror (no)—

“Observe the three, girl. One of these is at the beginning of writing—the archetrace: but we will never know which. The unanswered and unanswerable question—that undismissible ignorance—signs my authority’s failure. And I foresee the trialogue, now with one voice silenced, now with another overweeningly shrill, now with the three in harmony, now with all in cacophony, continuing as long as people cease to speak—and all speech is, after all, about what is absent in the world, if not to the senses—before the wonder, the mystery, the confusing, enciphered presence of a written text. But certainly you have seen these..?”

—what I’m saying is, is one of these (fantasy) is trying, Ringo, is trying real hard, to recapture (recover, receive, to understand) what has been lost, by trying to represent what is in what’s available, what’s been chosen; and one of these (SF) coolly abstracts what might well could be possible from what undoubtedly is, breaking through to a brave new world; and one of these (horror) is—is—is—