On the one hand; on the other.

From the opinion filed today in Juliana v. United States, 6:15-cv-01517-AA, reversing the certified orders of the district court and remanding the case with instructions to dismiss for lack of Article III standing:

Contrary to the dissent, we do not “throw up [our] hands” by concluding that the plaintiffs’ claims are nonjusticiable. Diss. at 33. Rather, we recognize that “Article III protects liberty not only through its role in implementing the separation of powers, but also by specifying the defining characteristics of Article III judges.” Stern v. Marshall, 564 U.S. 462, 483 (2011). Not every problem posing a threat—even a clear and present danger—to the American Experiment can be solved by federal judges. As Judge Cardozo once aptly warned, a judicial commission does not confer the power of “a knight-errant, roaming at will in pursuit of his own ideal of beauty or of goodness;” rather, we are bound “to exercise a discretion informed by tradition, methodized by analogy, disciplined by system.” Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process 141 (1921).

From the dissent:

Seeking to quash this suit, the government bluntly insists that it has the absolute and unreviewable power to destroy the Nation.

Freeze, peach!

How poetically telling, that the concept of kettling disruptive elements away in a First Amendment zone has been extended from protestors to reporters.

It is easier to clean the kitchen if you keep the kitchen clean

is one of those astringently parsimonious bromides that isn’t worth the wisdom it reveals, but I can’t help but think it applies to the problem with bringing back blogs. I couldn’t begin to tell you why I’ve suddenly resumed a former, blistering pace, but I can say that hiatuses be damned, this blog, this long story; short pier, is now old enough to vote in most American elections. Go on, then; have a haggis—

Message: I care.

The peculiar fusion of public and private, market forces and administrative oversight, the world of hallmarks, benchmarks, and stakeholders that characterizes what I’ve been calling centrism is a direct expression of the sensibilities of the professional-managerial classes. To them alone, it makes a certain sort of sense. But they had become the base of the center-left, and centrism is endlessly presented in the media as the only viable political position.

For most care-givers, however, these people are the enemy. If you are a nurse, for example, you are keenly aware that it’s the administrators upstairs who are your real, immediate class antagonist. The professional-managerials are the ones who are not only soaking up all the money for their inflated salaries, but hire useless flunkies who then justify their existence by creating endless reams of administrative paperwork whose primary effect is to make it more difficult to actually provide care.

This central class divide now runs directly through the middle of most parties on the left. Like the Democrats in the US, Labour incorporates both the teachers and the school administrators, both the nurses and their managers. It makes becoming the spokespeople for the revolt of the caring classes extraordinarily difficult.

I liked this, from David Graeber, which is of course about much more than last year’s depressing election in the UK. —It provides a certain clarity lacking in recent heated disputations, and recalibrates what’s seemed to be ineluctable math: I mean, if we’ve got to have an US and a THEM (and when there’s a fight, we do, yes, we do), then give us an US that everyone wants and a THEM no one wants to be (not so much the people that comprise it as the systems and rules and expectations, the bullshit, that generates and enforces the roles they end up playing; one is attempting, as ever, not to become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal). Care-giver versus administrator! (And not Brahmin Left versus Merchant Right, or PMC against Chapo Dirtbag.) —This a battle we all can join with a sunny heart.

The answer, I think, lies in the emerging structure of class relations in societies like England, which seems to be reproduced, in one form or another, just about everywhere the radical right is on the rise. The decline of factory jobs, and of traditional working-class occupations like mining and shipbuilding, decimated the working class as a political force. What happened is usually framed as a shift from industrial, manufacturing, and farming to “service” work, but this formulation is actually rather deceptive, since service is typically defined so broadly as to obscure what’s really going on. In fact, the percentage of the population engaged in serving biscuits, driving cabs, or trimming hair has changed little since Victorian times.

The real story is the spectacular growth, on the one hand, of clerical, administrative, and supervisory work, and, on the other, of what might broadly be termed “care work”: medical, educational, maintenance, social care, and so forth. While productivity in the manufacturing sector has skyrocketed, productivity in this caring sector has actually decreased across the developed world (largely due to the weight of bureaucratization imposed by the burgeoning numbers of administrators). This decline has put the squeeze on wages: it’s hardly a coincidence that in developed economies across the world, the most dramatic strikes and labor struggles since the 2008 crash have involved teachers, nurses, junior doctors, university workers, nursing home workers, or cleaners.

And if this move seemed odd, a bit redundant, somewhat unnecessary—“service work” does a fine-enough job delineating that US as it is, and of the three classes he’d cleave away (clerical, administrative, supervisory), it’s only ever really the clerical that gets fitted with a pink collar—the need to refine gives us just enough room to make sure the “care” in care-giver’s expansively defined, increasing our US, decreasing THEIR thems.

Whereas the core value of the caring classes is, precisely, care, the core value of the professional-managerials might best be described as proceduralism. The rules and regulations, flow charts, quality reviews, audits and PowerPoints that form the main substance of their working life inevitably color their view of politics or even morality . These are people who tend to genuinely believe in the rules. They may well be the only significant stratum of the population who do so.

But of course I’m going to latch onto this: I’m a professional manager in a decidedly PMC workplace—but a workplace with a mission to give what care we can to folks cataclysmically enmeshed in those rules, those regulations, those procedures, our laws. —I know which side I’m on, y’all. I know where I need to stand.

Comforts th’ comfortable; afflicts th’ afflicted.

“It may seem like humorless scolding, but the consequences of this type of demonization are real. A key feature of these stories—as seen in follow-up stories about the Taco Bell break-in by The Atlanta Journal Constitution, Fox 5 Atlanta, and several others—is mug shots that spread to hundreds of websites complete with the arrestee’s name. As I’ve reported elsewhere, this process of ‘mugshot shaming’ ruins lives and stains one’s online reputation for decades to come. At the other end of these clickbait stories is a real human being, and to the extent that these are ‘news,’ they are only so because the police see to it that they are.” —Adam H. Johnson

Okay, I don’t understand what this is. There’s a big-wheel truck, there’s a bad guy, there’s a doctor in a mini-dress, and there are bouncers.

I mean, I suppose there are worse things one could do with one’s time than to spend a year of it writing an essay a day about Road House…

Having the right to play.

“But Rosie nevertheless holds on to her joy at being alive. That joy isn’t naïve, or rooted in a denial of reality. Rather, it is an act of defiance, which makes a more powerful anti-fascist statement than any of the film’s mockery of its Nazi characters—a refusal to be made cruel and dejected by a world that has turned into a nightmare. ‘Welcome home, boys! Go kiss your mothers!’ Rosie cheerfully calls out to a truck full of defeated, injured soldiers headed into town, and when asked what she’ll do when the war ends, she answers, ‘dance,’ even as she lessens her odds of reaching that day by hiding Elsa, and leaving messages of defiance around the town. It’s not the sort of story one tends to see about this period, and I couldn’t help but wish that it was the story Jojo Rabbit had chosen to tell.” —Abigail Nussbaum

“The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal their bread.”

After more than two years of frustration from people who live in houses and in tents along interstate corridors, the city of Portland will take over campsite cleanup duties from the state transportation department.

Residents were baffled over whom to contact about trash, needles and other issues they saw along multi-use paths and sidewalks that run along highways. The city had no jurisdiction to clean up homeless camps, and the Oregon Department of Transportation was hard to get ahold of and slow to act, residents complained.

Meanwhile, homeless people who wanted an out-of-the-way spot to stay for a few nights said that they were never referred to social services and often didn’t know whose cleanup schedule they would be rousted by.

Wednesday, the Portland City Council unanimously approved an agreement with the department of transportation to use the city’s One Point of Contact system to field complaints and prioritize them for cleanup on the city’s schedule.

The partnership also brings a change in the schedule. Campsites will be notified that contracted crews will come to bag garbage and move tents at least 48 hours prior.

That is a compromise between the city’s 24-hour posting minimum and the state’s 10-day notice.

That went down just over a year ago. And it sounds lovely, doesn’t it? A decision that alleviates frustrations, providing clarity to both the people who live in houses, and the people who live in tents?

As Mayer tells it, earlier in 2019, Debbie had hip surgery and “was released to the street.” In July, Debbie, together with her husband Scott, and a number of other houseless people, were camped along a fence line in Southeast Portland, in close proximity to the Sunnyside Community House, where she found community, a couch to crash on, and coffee and warm meals.

“She was just a feisty, wonderful, strong woman,” Mayer said, “but she couldn’t walk very well for the last few months.”

In mid-July, the campsite was swept by the city-contracted Rapid Response Bio-Clean team, and, Mayer recounted, Debbie “lost all of her meds that day. She was on a series of eight or nine medications,” including antidepressants and insulin for her diabetes. “She lived her last days without them,” said Mayer, detailing the arduous lengths that houseless people have to go to in an effort to reclaim items taken during sweeps—from the last of their family photos, heirlooms and mementos, to ID and life-sustaining medications like insulin. People are not always able to retrieve the items, and in the cases when they are able to retrieve them, the items are sometimes contaminated and unusable.

The city mandates 48 hours’ notice before sweeps teams are allowed to move on the scene. A 48-hour window for moving, if you haven’t been on site for long, might not be that challenging if you’re in your 30s and don’t have any number of disabilities and health issues that are so common on the street. Of course, according to a recent study in Lancet, which encompassed multiple countries, including the US, if you’ve been on the street for any length of time, the odds are pretty good, about 53%, that you will have suffered a traumatic brain injury, whether before or in the course of being homeless. And if you’re pushing 60 like Debbie, a diabetic struggling with depression, in the midst of recovering from a hip operation, toting around the last of your worldly possessions, 48 hours might be a bit of a challenge.

But 48 hours is the mandatory window for notice before the team arrives to scour the scene. The 48-hour notice, Mayer tells me, doesn’t apply if the site has been swept within the past 10 days. So on July 24, Rapid Response returned to the site unannounced. And with no one about, they began taking down and collecting tents, whereupon they discovered the body of Debbie Ann Beaver.

Mayer said the Rapid Response team “noted her as deceased and did not attempt to revive her.”

I spoke by phone with Lance Campbell, the owner of Rapid Response Bio-Clean, who informed me that on discovering Debbie’s body, the workers, who were not trained in CPR, immediately called 911. He indicated that the police arrived on the scene within a few minutes and sealed off access to not only the tent but to the broader area, cordoning it off with police tape.

Mayer said no ambulance ever appeared on site, and at some point, Debbie’s body was placed in an unmarked white van, “and everybody just drove away. All the police disappeared at once, and nobody said anything to anybody.”

The catfish kept them fresh.

I appreciate this appreciation of Catfish (and now I know the story behind the title behind the term), and where it goes with it, but mostly I’ve got to admit I’m here for the story of Whitney and Bre—

Whitney and Bre are black queer women who have been in love for over four years without ever meeting face-to-face. Whitney lives in New York and works at Wendy’s six days a week to support her mom and four brothers. Bre lives in Los Angeles and is unemployed. In a truly genius plot, Whitney pretends to be a hopeful so that MTV will pay for them to finally meet. “I just get so freaked out when people can just sit across from you and lie like that,” says host Max, after uncovering hundreds of messages and video calls between Whitney and Bre. After much deliberation, the hosts decide to be chill because Catfish is a show about love and sometimes love makes people lie on reality TV. In the episode’s epilogue, we see Whitney and Bre strolling through a Los Angeles park. Their joy at finally being able to kiss and hold each other is palpable. I love Whitney and Bre. I hope they always love each other. I hope they never stop scamming corporations.

There ain't no such thing as a backyard leftist.

“As Washington Monthly points out, Hogan wins praise from ostensible liberals for being a ‘Republican who believes in climate change,’ but his administration has devoted itself to constructing automobile infrastructure over public transit. This is one of the most difficult things to get American voters to believe, but if you support state politicians who constantly build and expand highways, you do not support mitigating climate change. Larry Hogan may ‘believe in’ climate change, but he does not wish to do anything to stop it, especially if accelerating it is good for his own bottom line.” —Alex Pareene

“—que combina Realismo Mágico con Prosa Gonzo Noir—”

Oh, God, it’s been a good long while since I properly waxed utopian about art, and the internet, and what the internet does to art, and making art, making the making of it more possible, and making it available to anyone anywhere anytime anyhow, and if nobody was going to get filthy Stephen King rich anymore, well, how many were under the old paradigm, come on, we are all ’zinesters now, famous for fifteen people, hooray. (Link to youthfully mawkish manifesto thankfully removed.) —I mean, who saw the pivot to video coming? The rise of streaming? Back in those heady early days, we’re talking season four of Halt and Catch Fire, who could possibly have thought the World Wide Web Consortium would write DRM into the very backbone of the internet?

But though I may not so much talk the talk these days, I do still walk it: everything here is free, of course, because, I mean, my God, it’s a blog, but so is everything at the city: I mean, I’ll sell you a ’zine, charging a bit of money to cover not the story, but the printing and the collating, the folding and the stapling and the postage, and I’ll sell you an ebook if you like, but the whole thing from the get-go’s been available for free, because. —Not entirely free, mind: copyright is claimed, but the rights reserved are limited, as defined by a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 license, which means: so long as you say where you got it, and don’t use it for any commercial purpose, and let anyone else do the same with whatever it is you make of it—you can make of it whatever you want.

Such as, for instance, a translation.

David (Artifacs) from Spain has gone and taken advantage of this to do precisely that, translating the whole thing into Cervantes’ mother tongue, offering up to the panhispanic community Ciudad de las Rosas: “Despierta…” and El Fugor del Día and, coming next month, En el Reino de la Buena Reina Dick. And it’s a decidedly odd feeling, knowing “my” words are out there now in a language I can’t read, in sentences I can barely even begin to fumble through before reaching for a dictionary—

Cuando suena el teléfono, las arrugadas mantas se sacuden y retuercen y escupen una mano. La mano busca a ciegas, encuentra el despertador y le da al botón de «Snooze». El teléfono vuelve a sonar. Aparece una cabeza, parpadeando, aturdida. El cabello es rubio recortado cerca del cráneo, con un par de mechones largos aquí y allá, teñidos de negro, lacios. El teléfono vuelve a sonar. Ella se echa sobre él, medio cayendo del futón, agarra el auricular. “Qué”, grita.

(Note: just because I do freely offer up some rights doesn’t mean I wouldn’t be open to selling some others, should a streaming netlet desperate for content want to talk about pivoting to video. Call me. I’ll drum up some people to talk to your people.)

Adventures in Ego-surfing.

“When Pier 1 rocketed to popularity in the ’80s and ’90s, and again after the 2008 financial crisis, its competitive advantage was that it provided a combination of fashionable but affordable furniture and unique and charming home décor items that were difficult to find elsewhere. Pier 1 goods were higher quality than lower-priced competitors, but more affordable than designer brands. That moat has disappeared over the past decade as the market noted the popularity of such items and began mass-producing them for far cheaper. Long story short, Pier 1’s economic moat has disappeared, and its profitability has gone along with it.” —Margaret Moran

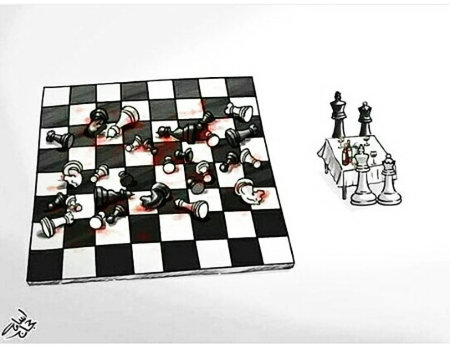

One-dimensional chess.

“No amount of brute force can hold the neoliberal order together—and Trump is not trying to hold it together. Rather, he and his fellow nationalists aim to ensure that the conflicts that succeed the neoliberal order will play out along ethnic and national lines rather than uniting everyone against the ruling class he represents. Case in point: the Iranian government, threatened by massive unrest scarcely two months ago, can now use the escalating conflict with the US to legitimize its authority domestically.” —CrimethInc.

A bad memory of policing in this country.

“But it changed our family, even if we never discussed it. We no longer spoke Farsi in public. My mom stopped saying hello to our neighbors as she got the mail. My dad lowered the Persian dance music from his car stereo before turning onto our street. My brother, Sohrab, began to go by ‘Rob.’ And I borrowed the interests of my white peers: Lunchables, cheerleading and country music. I changed the way I dressed to fit in with the Abercrombie & Fitch girls in my class. I chemically straightened my thick, curly hair until it flowed straight down my back in sleek strands. I second-guessed the food I ate at lunchtime: Persian stews served with rice were swapped out for PB&J sandwiches in brown paper bags.” —Farnoush Amiri

“It doesn’t matter that we started it”

Over on the Twitter, Lili Loofbourow reminds us of this cracking David Graeber essay, on bullying, and power:

Here I think it’s important to look carefully at how institutions organize the reactions of the audience. Usually, when we try to imagine the primordial scene of domination, we see some kind of Hegelian master-slave dialectic in which two parties are vying for recognition from one another, leading to one being permanently trampled underfoot. We should imagine instead a three-way relation of aggressor, victim, and witness, one in which both contending parties are appealing for recognition (validation, sympathy, etc.) from someone else. The Hegelian battle for supremacy, after all, is just an abstraction. A just-so story. Few of us have witnessed two grown men duel to the death in order to get the other to recognize him as truly human. The three-way scenario, in which one party pummels another while both appeal to those around them to recognize their humanity, we’ve all witnessed and participated in, taking one role or the other, a thousand times since grade school.

The application of which to our current moment is made historically clear from the jump—

In late February and early March 1991, during the first Gulf War, US forces bombed, shelled, and otherwise set fire to thousands of young Iraqi men who were trying to flee Kuwait. There were a series of such incidents—the “Highway of Death,” “Highway 8,” the “Battle of Rumaila”—in which US air power cut off columns of retreating Iraqis and engaged in what the military refers to as a “turkey shoot,” where trapped soldiers are simply slaughtered in their vehicles. Images of charred bodies trying desperately to crawl from their trucks became iconic symbols of the war.

I have never understood why this mass slaughter of Iraqi men isn’t considered a war crime. It’s clear that, at the time, the US command feared it might be. President George H.W. Bush quickly announced a temporary cessation of hostilities, and the military has deployed enormous efforts since then to minimize the casualty count, obscure the circumstances, defame the victims (“a bunch of rapists, murderers, and thugs,” General Norman Schwarzkopf later insisted), and prevent the most graphic images from appearing on U.S. television. It’s rumored that there are videos from cameras mounted on helicopter gunships of panicked Iraqis, which will never be released.

It makes sense that the elites were worried. These were, after all, mostly young men who’d been drafted and who, when thrown into combat, made precisely the decision one would wish all young men in such a situation would make: saying to hell with this, packing up their things, and going home. For this, they should be burned alive?

—our “current,” eternally returning, horizon-closed, Groundhog-Day’d moment.

And sure, tell yourself Trump’s the bully, and we’re the witness, the audience, but Trump is also very much the audience, being appealed to by Pompeo and the Fox Newsocracy as they ’it ’im again—the soul of our nation (such as it is), the lives of thousands if not millions of people, will be battled over by our very own self-inflicted Haw-Haw, and Tucker fucking Carlson, and I’m not sure where Chris Hayes fits into this trialectic—

—but he works for an organization that fired Phil Donahue for far less reason than they ever had to fire Matt Lauer.

This is difficult stuff. I don’t claim to understand it completely. But if we are ever going to move toward a genuinely free society, then we’re going to have to recognize how the triangular and mutually constitutive relationship of bully, victim, and audience really works, and then develop ways to combat it. Remember, the situation isn’t hopeless. If it were not possible to create structures—habits, sensibilities, forms of common wisdom—that do sometimes prevent the dynamic from clicking in, then egalitarian societies of any sort would never have been possible. Remember, too, how little courage is usually required to thwart bullies who are not backed up by any sort of institutional power. Most of all, remember that when the bullies really are backed up by such power, the heroes may be those who simply run away.

Your tongue is no one else's tongue.

When I said “flavor’s the very essence of a sylph,” this is something of what I was getting at: “The first time I ate at Carbone, the nostalgia-steeped temple to red-sauce Italian that opened in 2013 in New York’s Greenwich Village, I was two Gibsons in when my penne alla vodka arrived, and I took my first bite, a transcendent roundness of cream and tomato and heat, just as the Cavaliers’ ‘Last Kiss’ started playing on the sound system. My contentment in that moment was so comprehensive, so powerfully complete, that I was horrified to realize that I was crying—weeping literal, actual tears—as I ate my meal, one of the loveliest and most profound of my life. When I came back a few months later, repeating my order to the letter, it was just a nice plate of pasta.”