Terrifyingly serious, casually bigoted, deliberately absurd:

“Since the murder of Heather Heyer by a white supremacist in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August of 2017, I’ve been regularly watching discussion boards on 8chan and the neo-Nazi website Stormfront to better understand what I call ‘8chan Medievalism.’ I wanted to examine how the worst people in the world talk about the Middle Ages within their own Internet safe spaces. What I’ve found is that the problem has gotten worse online, even as 8chan medievalism has shown up in the writings of mass-murdering terrorists and would-be terrorists.” —David M. Perry

High turnover, low inventory, mostly cash—

a Sunday afternoon seminar in money laundering (twitter; threaded) that starts with a weed dealer and a sub shop, and ends with the bulk of the wealth of the world. Your basic TL;DR: “If we were serious about crime, we’d take most of the cops off the streets and replace them with accountants. Taking down the financial underpinnings of a criminal enterprise is way more effective than busting their entry level contractors.”

Devoted to Doers and Doings.

Bit odd to see a write-up in Forbes for D. Vincent and Meguey Baker, friends of the pier (and the city), and game designers par excellence nonpareil—though one is now drily amused at the thought of vulture capitalists pondering how best to monetize indie games. (They’re invited to peruse this list, to start.) —Here’s a neat presentation on (some of) what goes into being Powered by the Apocalypse; go, play.

He said, he said.

People like you are still living in what we call the reality-based community. You believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality. That’s not the way the world really works anymore. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you are studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors, and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.

—a senior advisor to Bush fils, as interviewed by Ron Suskind

No. When you have power, you don’t take responsibility for abusing others. You enjoy the power. That’s the way it works in reality.

—Terry Gilliam, as interviewed by Alexandra Pollard

The strengths of prose.

More writing about stuff I’ve yet to see! —I mean, I’ve heard good things from people I don’t disrespect about The Expanse on the teevee; heck, I think the Spouse has seen some episodes, but then, she is a bit more committed to life-in-space stories than I am. (I checked; she saw the first few episodes. “It had promise,” she says.) —But life is short, there’s too much to watch as it is, and between my distrust of corporate media ever being able to do anything actually good with Workers Uniting, and the vague whiff of Detective Snapbrim’s Manpain in Space, I’ve just never bothered.

As for the books: again, short life, so much to read, life-in-space, the Walter Jon Williams is somewhere in the TBR though, so there’s that, and I’ve got all those Transhuman Space and 2300 sourcebooks under my belt. —I have read some Daniel Abraham, though, who’s one half of James S.A. Corey, who writes the Expanse books, but I read him when he was MLN Hanover, and I was trying to figure out what was happening or had happened to «urban fantasy» while I was in the kitchen, getting coffee, and though I’ll always tip my hat to him—to Abraham, that is—for the pith of “Genre is where fears pool,” I’ll always then step back with a quirked brow at where he went next with that.

But! We’re not talking about lupily dhampiric gamines in Eddi and the Fey T-shirts, and we’re not talking about stylish snapbrims in space—we’re talking about adapting a work from one medium to another, and that, well—

Goodreads:

What was the biggest challenge when adapting your novels to the screen?Daniel Abraham:

The books were really written to lean into the strengths of prose. They’re full of interior monologue and clarifying exposition that just don’t work on camera at all.

—it turns out I have plenty of strong opinions about that.

To say that this or that is something so strong as the strength of something so very expansive as prose is perilously close to making an essentialist argument, and while I’d never tell you not to make one of those, one really ought to state outright what the essence is of the thing in question, and the essence of prose is setting down one word after another—which has nothing in and of itself to do with either clarifying exposition, or interior monologues. —Certainly, one can exposit or monologue in prose, and, depending on the idiom, mode, and genre in which one finds oneself, and the reading protocols thereof, and the expected and unexpected audience expectations, and whether one chooses to cleave to them, or cleave them, one may well find it an easy enough thing to do. But don’t let’s kid ourselves it’s a strength of the medium.

As to whether it’s a weakness anywhere else—

—sure, sure, you say monologue and you say cinema and you immediately think voiceover and you think theatrical cut of Blade Runner and you think you’ve won the argument, but then—

—so don’t tell me it “don’t work on camera at all.”

(As for exposition, clarifying or otherwise: one is reminded that, when John M. Ford wanted to exposit some details of dilithium in his Star Trek novel, How Much For Just the Planet?, he did so by way of the narration of an educational filmstrip titled “Dilithium and You,” but that’s a prose transcription of a visual medium inside a novelization of a television show, and I’ve lost track of where we were, and anyway Paramount changed the rules after it came out so nobody could ever do that again.)

This may seem like an awful lot to unpack from an offhand comment; Abraham’s not without his point. The expectations of any audience here and now for a series of SF books such as the Expanse allow for certain techniques that an audience here and now for an SF teevee show would balk at, and the expectations that underlie such an observation, the reasons one might put forward to explain it, could be fascinating to work through—but flatly stating that this is a just-so strength of prose, and would never just-so work on camera, utterly occludes the possibility of that work (that play).

But such a conversation is well beyond the scope of a hype interview on the occasion of a fourth-season premiere, so let’s allow as how they’re maybe just speaking imprecisely, in haste, as we all have done, and move on—

Ty Franck:

It’s also given us a chance to learn how to use the strengths of TV to tell the same story in a different way. I know Daniel had a real epiphany when he realized that all the prose tricks to convey the emotional state of a scene could be replaced with a good musical score.

—yeah. Okay. Sorry. You’re on your own with this one.

Resolution.

“The Decade from Hell has put us further down a path toward both national and planetary ruin. It has, however, also offered numerous stories that can guide us in a new direction—stories about the power of ordinary people coming together to present the moral cases for change and demand that the powerful act on these cases. There is no substitute, even in this digital age, for direct action. The best remedy for business as usual remains making business as usual impossible.” —Osita Nwanevu

The war that will end war.

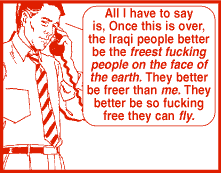

We’re a fifth of the way into the 21st century, and Chris Teso, founder of Chirpify.com and guest-columnist for Oregonlive.com, wants us to end our war on cars. —I used to have to commute in a car, and am thankfully blessedly once more in the position of NOT HAVING TO, of being able to catch one of the regular busses that stops just about right outside my house, or even when the mood takes me walking leisurely over the river and into downtown to get to work, and this is a luxury, I know, but one I’d share with everyone I could, and I stare perplexed at those who think they’d willingly turn it down for a chance to sit ensnarled in choking traffic: who does that? (People who seem to think having to sit next to a stranger on a bus is somehow an invasion of privacy, but we digress.) —I’m glad folks elsewhere took note of this entitled little screed, and took issue with its faulty logic and framed statistics, because damn: we’d do so much better to actually fight a war on cars, instead of all our wars for cars—I mean, can you believe this old bumper sticker is still searingly fucking relevant?

Rise of Something-or-other.

I don’t read novels. I prefer good literary criticism. That way you get both the novelists’ ideas as well as the critics’ thinking. With fiction I can never forget that none of it really happened, that it’s all just made up by the author.

So in other news of the-criticism-of-things-I-have-no-intention-of-seeing-myself, the Laverys went to see the new Star Wars and then had a conversation about it, and why would I subject myself to almost three hours of G-mergate capitulation when instead I could enjoy a frothy interplay of ideas that careens from Grace, taking up the question Lili Loofbourow asked, back when the first (the seventh) first came out—

The thing that has stunned me about Star Wars, for decades, has been the franchise’s extreme casualness about mass death. In The Rise of Skywalker, someone destroys a planet as a kind of flirtatious joke—“This’ll light a fire under their asses!”—and the effects of that catastrophe disappear from the screen within a couple of seconds.

—to Daniel’s reaction to (the lack of) the queering of (the lack of) Finn and Poe—

All I can think of with that “two men refusing to kiss? That’s a story” is the old “headless body found in topless bar” bit about what makes for really good headlines. I picture Sedgwick in full JJ Jameson drag, complete with cigar, yelling over the phone: “Two men refusing to kiss? Get me the photographs!”

—so anyway. Go; read.

Sed quis non custodiet ipsos custodes?

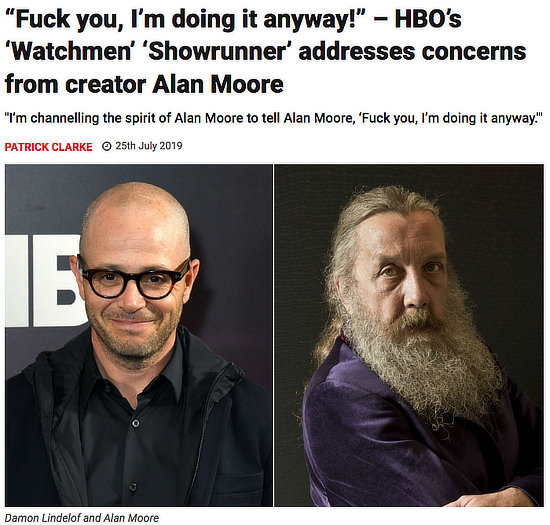

If I have to hear one more goddamn television producer insist their multimillion-dollar teevee show is really, truly punk—

—I swear to fucking God—

I’m afraid that for a few years now, I have felt that since I am apparently not allowed to own the work that I created in the same manner that an author in a more grown-up and worthwhile field might expect to do, and since my protests at having my work stolen from me are interpreted by a surely young-at-heart and non-unionised audience as evidence of my “grouchiness” and “cantankerousness,” then the only active position that is left to me is to disown the works in question. I no longer own copies of these books and, other than the earnest creative work that I put into them at the time, my only associations with these works are broken friendships, perfectly ordinary corporate betrayals and wasted effort. Given that I will certainly never be reading any of these works again and that I have no wish to see them or even to think of them, it follows that I don’t wish to discuss them, sign copies of them or, indeed, have anything to do with them. As I would hope should be obvious, to separate emotionally from work that you were previously very proud of is quite a painful experience and is not undertaken lightly. However, having to answer questions about my opinions regarding DC Comics’ latest imbecilic use of my characters or stories would be much more harrowing. And, of course, it’s not as if I don’t have plenty of current work to be getting on with.

—so yeah, I was not shall we say well-disposed to the idea of a televisual sequel to Watchmen. Sure, by all accounts it was gonna be better than the last attempt to frack monetary value from the IP’s shale (but Christ, Zack Snyder is such a low bar), and I will admit my resolve (if such a curmudgeonly disdain might be dignified with such a word) weakened when I heard what they’d managed to pull off with Hooded Justice, but then I heard what they did with Laurie and Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias and Angela Abar and Lady Trieu, and my resolve redoubled.

Should we be surprised that Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen made Lady Trieu the bad guy? That a character named after Bà Triệu, a legendary third-century nationalist hero who resisted the Chinese occupation of Vietnam, must in the end be stopped by the combined efforts of two white men associated with the genocidal destruction of multiple civilian populations (the Manhattan Project, the bombing of Vietnam itself, and the squid-fall of New York)? Should we be surprised that a show which began with an airplane dropping bombs on Tulsa provides narrative closure by thwarting Trieu’s evil plans with “a gatling gun from the heavens” fired at Tulsa? (The gatling gun, briefly used in the American civil war, and extensively used in colonial subjugation.) How did Lady Trieu, would-be avenger of colonial-violence-from-the-heavens, become the victim of yet another righteous iteration of death from the skies?

That’s from Aaron Bady’s wrap-up at the LARB, which is exactly what you’d expect from him on something like this with a title like that. —Just because I’m not gonna bother watching the show doesn’t mean I’m not going to read what people have to say about it, much as I’ve been staring agog at every Skywalker spoiler that seeps within my purview (they fucking did what now with his futhermucking X-wing?). —The one that’s stuck with me the most, most recently, has been Jaime Omar Yassin’s “Black, White, Blue”—

Lee characterizes the print Watchmen as a brilliant, subversive anti-racist and anti-fascist text that Lindelof’s TV show fails to live up to. I loved Moore’s Watchmen and have re-read it half a dozen times over the years, and that’s why I’m confident that the original text is a really unfortunate platform to launch these critiques from.

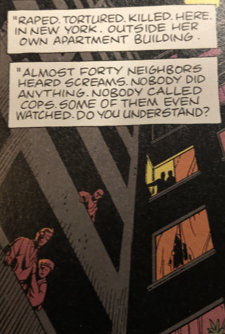

Moore built an ugly super-hero landscape, mired in imperialist politics, narcissism, cultural chauvinism and white supremacist zeitgeists, true. The birthplace of superheroing is the “Minutemen” a WW2 era group of morally-confused and easily-corrupted narcissists working under a white supremacist, capitalist definition of right and wrong who donned capes for uninspiring reasons. Moore’s work has always been about taking apart superhero tropes and putting them back together in situations atypical of the genre (1). But Moore went a few steps further here because he was able to sully the intellectual property and express his own politics about the concept. And he did it beautifully—Watchmen transcended the form with its intricate plot and a reverberating flow of prose and art. All indisputable.

Regardless of his intentions, however, Moore built a thematic framework that bolsters many awful superhero tropes—and these have outlived the subversive qualities of the text (2). Moore, to his credit, created dynamic three-dimensional characters, and that’s the problem. After all is said and done, Dr. Manhattan is a mass murderer indifferent to human suffering. Rorschach, a proto-incel, is an Alex Jonesian conspiracy-fabulist. And yet fans—like me—loved them both for decades. Moore had us spend so long in the heads of Manhattan and Rorschach that eventually their world-views became compelling.

Omar deftly explicates the comic’s whiteness, and its failures to address race and racism (despite its aims and goals), and ties this to a general pro-police tenor in Moore’s work—surprising, to be sure, in an anarchist; less so, perhaps, in a writer of superhero comics: and this, I think, is where the dam’ whole enterprise falls down: “The fail condition of subversion/parody is reification.”

But I want to dig into one thing Omar brings up that reveals just how heartbreakingly Watchmen fails, or was failed—

Rorschach is every bit the reactionary Miller’s Batman is, but Moore’s superb narrative tells us why in a compelling and heart-breaking flashback. Ironically, Rorschach’s lengthy existential thought balloons (and those of Dr. Manhattan) feed into conservative ideas about a dark nature of humanity with a far greater lasting effect than Dark Knight Returns. Moore compounded this by taking Rorschach’s side in philosophical debates. When a “liberal” African American prison psychiatrist must treat Rorschach, it’s Rorschach’s perspective that infects him, not the other way around. Rorschach is shown to have the more compelling, self-aware view, while the psychiatrist is a liberal fop, as weak as Rorschach implies when he reads him. Moore—unlike Miller who actually got worse (3)—moved on from treatments of superheros in the decades after Watchmen, I suspect because he recognized the perils of even engaging the tropes (4).

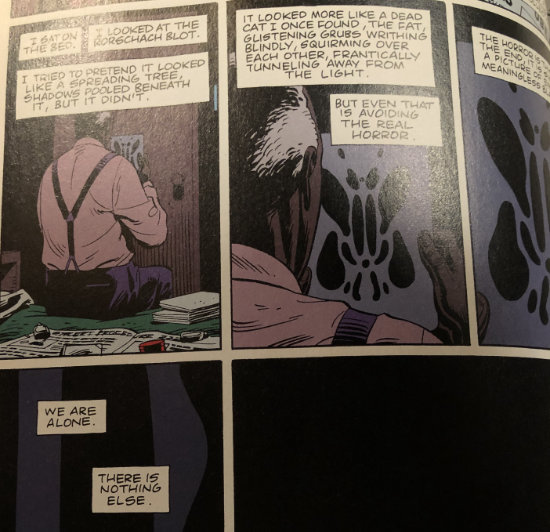

Aaaaand—I mean, it’s not that this isn’t not what doesn’t happen, and it’s not that Dr. Malcolm Long isn’t a liberal fop, a milquetoast, even, and it’s not that he’s not infected by Rorschach’s nihilism. But that’s not the end of Long’s story.

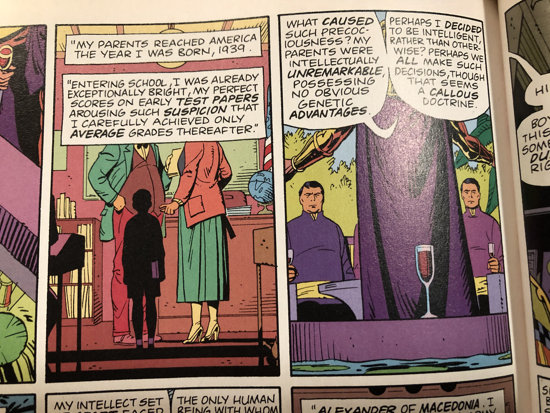

Rorschach’s (Kovacs’) “compelling and heart-breaking flashback” is, of course, built around, based upon the Kitty Genovese story—not what actually happened, but the story—

(And as a brief digression, the shot here, of neighbors watching from the balconies of apartments supposedly on Austin Street in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York, lends some slim credence to the mildly contested theory that Moore tripped over the story of Kitty Genovese by way of Harlan Ellison’s “Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” which, I mean, I know I first heard the story of Kitty Genovese by way of an Ellison essay, I think, in The Glass Teat, I think, which is one more I owe the bastard, and anyway, I agree with Joanna Russ—but let’s face it, the story of Kitty Genovese is everywhere.)

(And as a brief digression, the shot here, of neighbors watching from the balconies of apartments supposedly on Austin Street in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York, lends some slim credence to the mildly contested theory that Moore tripped over the story of Kitty Genovese by way of Harlan Ellison’s “Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” which, I mean, I know I first heard the story of Kitty Genovese by way of an Ellison essay, I think, in The Glass Teat, I think, which is one more I owe the bastard, and anyway, I agree with Joanna Russ—but let’s face it, the story of Kitty Genovese is everywhere.)

—though I must admit a moment’s amusement, reconciling the queer bar manager who was, with the socialite who was supposed to have been, who rudely rejected the pop-art op-art dress that ended up becoming what would be Rorschach’s mask.

It’s pointless to argue whether 38 or “almost forty” neighbors really heard the socialite’s screams, or if it was more like what really happened; what happened that was compelling and heartbreaking was that Kovacs read an article in the New York Gazette that said that’s what had happened, which is what inspires him to make his mask and dress up as Rorschach and go and fight crime as a costumed adventurer né superhero—“I knew what people were then,” he tells Dr. Long; “behind all the evasions, all the self-deception. Ashamed for humanity, I went home. I took the remains of her unwanted dress and made a face that I could bear to look at in the mirror.”

And Dr. Long hears that and tries to dismiss it and feels badly about trying to help Rorschach or Kovacs out of somewhat selfish reasons and has movie-of-the-week arguments with his wife about the damage his dedication to his job is doing to their marriage, and in the end he breaks on the bulwark of Kovacs’ or Rorschach’s next, real origin story, which I bet Zack Snyder got a kick out of filming—but that isn’t the end of Long. It’s just the end of chapter six. (Of twelve.)

No, Long’s end comes at the end of chapter eleven: as Ozymandias’s stupidly huge plot comes to fruition, a number of uncostumed unadventurous unsuperheroes whom we’ve seen here and there in the previous chapters milling about the business of their lives as the protagonists protagonize, these folks end up converging on a corner by Bernard’s newsstand near Madison Square Garden, Dr. Long, and Bernard (of course), and Bernie, Derf, Detectives Steven Fine and Joe Bourquin (cynical cops who in the end get to prove they’re good police, but I anticipate myself), Milo, Gladys Long, and Joey and Aline, and the point is, what happens is, when Joey and Aline get into a fight over their dissolving relationship, and when Joey attacks Aline, pushes her to the ground, starts kicking her, right there, on the sidewalk, before the newsstand, all those onlookers, those neighbors, less than 38 or almost 40, sure, but Bernard and Detective Fine and even yes Dr. Long, despite his infection with Rorschach’s nihilism, he steps up with the rest of them all to stop the fight, and that’s the end of Dr.Long, and all of them: a spontaneously anarchist fellowship, a striking reversal of a superheroic origin, a repudiation of all the cool grimdark Rorschach supposedly serves up as truth, a pro-Genovese anti–Genovese-story—

—that gets smashed in the very next instant, bigfooted by the squid-drop climax of the protagonists’ plot.

But! This ironic thematic climactic crescendo itself gets bigfooted by everything that happens around and about that squid-drop: the superhero-cool in Antarctica, “I did it thirty-five minutes ago,” Dr. Manhattan’s apotheosis and Ozymandias catching bullets and Rorschach in the snow. The book’s supreme irony—that the human fellowship Veidt despaired of is obliterated precisely by the plot that Veidt engineered to restore it—is itself ironically overwhelmed by the superheroic armature of that plot. So much so that almost no one who talks about it ends up talking about this at all…

I said this recently but I think the best part of the comic is all the background characters coming together to try to stop a fight in Times Square, on their own, no capes. https://t.co/iuyO0U5vMe

— Gerry Canavan (@gerrycanavan) December 9, 2019

…so that’s another way that Moore and Gibbons failed the comic (not so much Higgins, he’s still cool), and the comic failed the show, and the show failed us all, and as for us?

The Fanonian Watchmen is there, but buried deep. By quoting from the “The Internationale,” Fanon’s title gives to the Wretched of the Earth the implied imperative to “Stand up,” but Lindelof’s Watchmen submerges any revolutionary consciousness under things like the cartoonish “Red Scare” character. The only masses in the show are white supremacists. Still, if you look for it, you can find in the story of Angela and her grandfather the discovery that America’s problem is not hidden conspiracies to be revealed but the open secret of American white supremacy; if you want, you can trace out the show as it might otherwise have been, in which two granddaughters of American massacres team up to create a better world from the ashes of what was done to their families.

We’re left once again to ignore the ending we’ve been given, and imagine something else.

(Oh but one last ever-loving thing: learning that Lady Trieu’s villainous genius was explained and excused by her descent from Veidt was enough to make me want to throw the goddamn television show across the goddamn room. Why—that would be as astoundingly short-sightedly stupid as the Star Wars people deciding that instead of being her own person, Rey would have to be excused and explained by her descent from someone like Emperor Palpatine, I mean, can you imagine? —Can you imagine something else? Something different? —At all?)

Retrospectacular!

It’s that time of year, when those of us still in the blogging game tell you what we did with the previous three-hundred-sixty-five, much as many of us working the fantastika mines tell you which of what we’ve done is eligible for this award, or that. —But most of what I’ve done this past year has been over at the city, finishing the third volume; writing the thirty-third chapter. The blogging here’s been slight.

But it’s also that time of the decade, isn’t it? —Accepting for the moment that one can at once aver that decades don’t begin on the downbeat of the zero,

Let’s see: I made an opaquely definitive statement on URBAN FANTASY, that I later repurposed as a guest-post in a marketing push for vol. 2 (I have some strange ideas on marketing); I solved in one stroke both income inequality and global warming; I defined the most important social media trend of the decade (which promptly dissipated); I engaged in some criticism, like this, about Frozen, or this, about, um, Frank Herbert, and Reza Negarestani, or this, which is about just about everything, and had a DVD’s worth of cut scenes; and also I used the supreme cinematic accomplishment of 2008 to explain the Cluthian triskele; and also I had some things to say about publishing (mass-market, and self-); a friendly comment from an international correspondent led to a momentary spark of reason; I walked away from Twitter, which was supposed to lead to more blogging (I mean, it did, but not as much as maybe I’d thought, and also, see above); and, but, before I did, I turned some off-hand twitterings to things I rather liked, on novel-shaped objects, and galactic civilizations.

Also, I sold maybe the only story I’m going to sell, and—even though I got started before 2012, or even before the beginning of the decade, still: I published all three books in the past ten years; I wrote a goddamn trilogy. —So there’s that.

Minimally viable product,

or, Easy money at the ketchup factory.

“The books are wretchedly written, but fast-moving. The wretched prose, the mixed syntax, the bad grammar, and the typos would barely raise a sneer from the MFA-educated crowd. They’re used to a publishing industry that already embraces James Patterson and Dan Brown’s barely literate level of storytelling. The bar was already low; it’s just being slid through the wood chipper and scattered over the culture like salt at Carthage. —I looked up Anderle’s record on Amazon. His Author Rank is #54 in the Horror category, placing him ahead of Lee Goldberg, Seth Grahame-Smith, and some guy named “Richard Bachman.” In Science Fiction, he’s ranked #60, ahead of Alan Dean Foster, John Scalzi, Douglas Adams, and Neal Stephenson. —But if you feel that Anderle’s work represents the bottom of the barrel, you haven’t met T.S. Paul.” —Bill Peschel

Fuck death.

It hit me hard when Howard Cruse went and died, but I’d had no idea Tom Spurgeon was already gone—

This storm is what we call progress.

Many of the great fantasy writers of the last century were shaped by the experience of World War One; the attitude of JRR Tolkien to the world storm of his time is anguish and anger; he and other great fantasy writers turn away from the world to shame it. Here are the four phases:

- Wrongness. Some small desiccating hint that the world has lost its wholeness.

“With each set of three books, I’ve commenced with a sort of deep reading of the fuckedness quotient of the day,” he explained. “I then have to adjust my fiction in relation to how fucked and how far out the present actually is.” He squinted through his glasses at the ceiling. “It isn’t an intellectual process, and it’s not prescient—it’s about what I can bring myself to believe.”

- Thinning. The diminution of the old ways; amnesia of the hero and of the king; the harvest fails, the Land dries up; diversion of story into useless noise; battle after battle.

After The Peripheral, he wasn’t expecting to have to revise the world’s F.Q. “Then I saw Trump coming down that escalator to announce his candidacy,” he said. “All of my scenario modules went ‘beep-beep-beep—super-fucked, super-fucked,’ like that. I told myself, Nah, it can’t happen. But then, when Britain voted yes on the Brexit referendum, I thought, Holy shit—if that could happen in the UK, the US could elect Trump. Then it happened, and I was basically paralyzed in the composition of the book. I wouldn’t call it writer’s block—that’s, like, a naturally occurring thing. This was something else.”

- Recognition. The key in the gate; the escape from prison; amnesia dissipates like mist, the hero remembers his true name, the Fisher King walks, the Land greens. The locus classicus of Recognition is Leontes’s cry at the end of The Winter’s Tale (1610) on seeing Hermione reborn: “O she’s warm.”

In the hall, he relieved me of my misjudged chore coat, and handed me a recent reproduction of Eddie Bauer’s 1936 Skyliner down jacket: a forerunner of the down-filled B-9 flight suit, worn by aviators during the Second World War. Boxy and beige, its diamond-quilted nylon was rigid enough to stand up on its own. When I put it on, it made me about four inches wider. Gibson shrugged into a darkly futuristic tech-ninja shell by Acronym, the Berlin-based atelier, constructed from some liquidly matte material.

“You have to dress for the job,” he said.

- Return. The folk come back to their old lives and try to live them.

She doesn’t zoom through glowing datascapes; instead, having suffered from “too much exposure to the reactor cores of fashion,” she practices a kind of semiotic hygiene, dressing only in “CPUs,” or “Cayce Pollard Units”—clothes, “either black, white, or gray,” that “could have been worn, to a general lack of comment, during any year between 1945 and 2000.” She treasures in particular a black MA-1 bomber jacket made by Buzz Rickson’s, a Japanese company that meticulously reproduces American military clothing of the mid-twentieth century. (All other bomber jackets—they are ubiquitous on city streets around the world—are remixes of the original.) The MA-1 is to Pattern Recognition what the cyberspace deck is to Neuromancer: it helps Cayce tunnel through the world, remaining a “design-free zone, a one-woman school of anti whose very austerity periodically threatens to spawn its own cult.” Precisely because it’s a near-historical artifact—“fucking real, not fashion”—the jacket’s code can’t be rewritten. It’s the source code.

I think it’s inarguably clear: we must admit William Gibson to the ranks of the world’s great fantasists.

Regret, by definition.

I’m not sure what to say about this article about the reappearance of John M. Ford; chances are good you’ve already seen it, since it’s been out for almost a week now, and it shows up in the wee little sidebar on the Google news thing, which I assume means people want to see it enough that the algorithm has learned it’s what people want to see. —But I’m not gonna not put a link to it here; the days I don’t want to be Dorothy Dunnett when I grow up, I want to be John M. Ford; every time somebody quotes his line about his horror of being obvious, I feel entirely too seen. Maybe wind this up with a growl at, I don’t know, the Yankee health insurance system, or capital’s grinding gears, or pettily familial stupidities redeemed by an accidentally incandescent burst of good news: send tweet.

What I tell you three times is true.

The thirty-third installment’s been released: the eleventh (and final) chapter of the third volume, which means: I’ve done it. I’ve gone and written a trilogy.

And there’s work yet to be done and technical difficulties to overcome and I have to re-remember all the stuff about marketing and distributing book-shaped objects but for the moment I get to sit here on this deserted bit of beach as the tossing storm growls away over the horizon and take a deep breath and enjoy the silence, before I start vaguely to worry about what happens next. (An aftermath, yes, I do enjoy a good aftermath, but then what? And what then?)

—I guess I’d thought a Snark would have more meat on it?