Elsewhere, otherwise.

I should probably since I haven’t already point out that if you were so inclined you can also find me over on the Twitter, and I’ve been elbowing my way into conversations at the MetaFilter. Which might help to explain why the short-form’s fallow on the pier these days.

Further up; further, in—

But! Baby steps. Easing back into it and all. —Maybe the business with the maps?

The portal quest fantasy, per Mendlesohn (as opposed to an immersion, or an intrusion, or a liminal, or whatever else, and trust me, we’ll get there), is a didactic idiom: one that takes its necessarily naïve protagonist on a tour of the otherworld with a garrulous guide or guides who brook questions almost as often as interruptions. “Fantasyland is constructed,” she says, and we should be clear, she means Fantasyland is constructed in the portal-quest fantasy,

in part, through the insistence on a received truth. This received truth is embodied in didacticism and elaboration. While much information about the world is culled from what the protagonist can see (with a consequent denial of polysemic interpretation), history or analysis is often provided by the storyteller who is drawn in the role of sage, magician, or guide. While this casting apparently opens up the text, in fact it seeks to close it down further by denying not only reader interpretation, but also that of the hero/protagonist. This may be one reason why the hero in the quest fantasy is more often an actant rather than an actor, provided with attributes rather than character precisely to compensate for the static nature of his role.

Which, okay, and now let’s skip ahead a couple of pages—

This form of fantasy embodies a denial of what history is. In the quest and portal fantasies, history is inarguable, it is “the past.” In making the past “storyable,” the rhetorical demands of the portal-quest fantasy deny the notion of “history as argument” which is pervasive among modern historians. The structure becomes ideological as portal-quest fantasies reconstruct history in the manner of the Scholastics, and recruit cartography to provide a fixed narrative, in a palpable failure to understand the fictive and imaginative nature of the discipline of history.

Flip back a page or two—

Most modern quest fantasies are not intended to be directly allegorical, yet they all seem to be underpinned by an assumption embedded in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678): that a quest is a process, in which the object sought may or may not be a mere token of reward. The real reward is moral growth and/or admission into the kingdom, or redemption (althouh the latter, as in the Celestial City of Pilgrim’s Progress, may also be the object sought). The process of the journey is then shaped by a metaphorized and moral geography—the physical delineation of what Attebery describes as a “sphere of significance” (Tradition 13)—that in the twentieth century mutates into the elaborate and moralized cartography of genre fantasy.

—which paragraph ends neatly enough with—

In any event, the very presence of maps at the front of many fantasies implies that the destination and its meaning are known.

—and, well, yes, okay: I mean, you open just about any wodge of extruded fantasy product these days and yes, there it’ll be, the map, or at least it used to be that way; maybe it’s fallen out of fashion these days? —Doesn’t matter. The ghost of it’s damn well there. There’s always been a map.

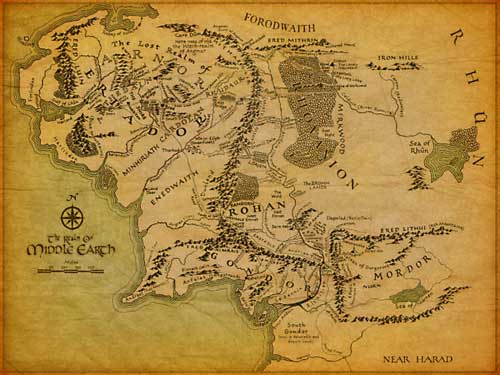

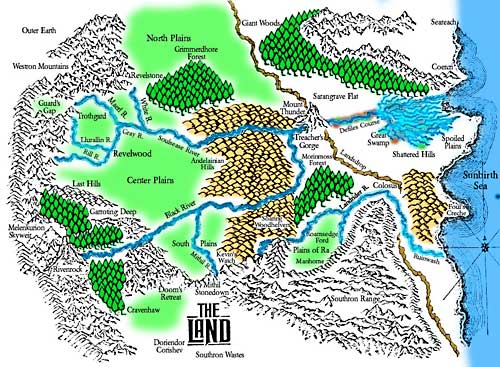

And maybe it isn’t too clear, immediately, on the map in Papa Tolkien’s tome, how the process of the journey is laid out, how it is exactly the geography’s metaphorized and moralized. But pull out some more maps, pore over them, look at how the Skull Kingdom’s always behind the Knife Edge Mountains—

—how the Soulsease River flows through Treacher’s Gorge and Defiles Course into the Sunbirth Sea—

—and you can start to see it; look more, look further back, scrub away the distractions of mountains and trees and lakes and look just at the map itself—

—and you can start to see the sphere of significance plain and clear, on which then the story of the quest of our hero(es) can be, well, mapped—

—a bildungsroman unspun in space, not time. You will go here, and have this adventure; go there next, and meet this companion; you will face physical hardship in the mountains, then inner turmoil in the deep woods, and if there’s a city, there will almost always be a seige, and a tower, and a coronation. Go and look at Papa Tolkien’s map again, and keep what you know of the story (of story itself, even) in mind (you know the story; the thing about this sort of thing is you’ve yes always already known it), it becomes clear that the destination and its meaning are known, are written there before you, that there was only one way it could ever have ended, once you started in the bucolic upper left; you had to sweep down and down to those snarling mountains in the lower right, and the city of Gondor gleaming there, where you might find your reward. —Didactic, fixed, moralized, metaphorized; cartography has been recruited, yes yes.

But—

Maps were my protonovels. I was reading Tolkien, and it was the maps as much as the text that floated my boat.

Mendlesohn, and this is important, is describing an effect of the rhetoric of the portal-quest fantasy. And it is a terribly important and I would even say o’erweening effect; she is not wrong to highlight it and draw protective circles about it thrice and thumb its forehead with penitent ash. The didacticism, the storyable past, the moralized geography, the protagonist as actant, the you-must-do-as-you-are-told-to-save-us-all (to reach the Celestial City, to redeem yourself)—this (if I might stuff it all into a singular word) is the supreme weakness of the portal-quest, and because the portal-quest is even now the supreme idiom of fantasy, is even now all of what most of us know of fantasy at all, this effect she’s described must therefore be addressed one way or another by every phantastickal book on the shelf.

But it’s hardly the intent of the naïve protagonist, the travelogue through fantasyland, the expository wizard, the map on the frontispiece. —Nor is it anywhere close to the only effect this furniture, these bits of business, might have on the reader, and the reading.

I’ve embedded images of these books because they offer, in various ways, some of the visual appeal which takes hold of readers of LOTR, The Hobbit and so on; Tolkien was susceptible to the paraphernalia of scholarship, to maps, manuscripts, the annotations which triangulate desire on such artifacts as objects of retrospection to a more heroic time—one constructed as real through the survival of such relics. For a certain sort of reader, scholarship is glamorous because reinforcing l’effet du réel.

The intent (an intent) is to take us readers by the hand and lead us from the world as it is out and away beyond the fields we know, and the simplest, easiest, most direct way to do this is to put fantasyland Out There and lead us through it, dragged along behind a protagonist who doesn’t know much more than we do, who must have stories told to them (and us) about the things they see, and because we are traveling about together in this other world, well, why not a map? That artefact of traveler’s journals ever since travelers began keeping journals. (Did every traveler keep a journal? I mean, all of them? How long ago did they begin, anyway? Were they really journals, or were they more reflections written long after the travels that spawned them? Or, y’know, propaganda, or marketing collateral, or—)

—To insist that history is multivocal, is an argument to be taken up and not a story that is dictated, is, well, is correct; to castigate this simple, brute-force technique for lulling a reader into the fields beyond as not living up to this basic truth of how we know what it is we know is, well, is also correct—but it overlooks the fact that the many and varied voices that carry out this argument of history, these arguments with history, are carried by books upon books within books echoing off books.

Most fantasylands are lucky to get just one.

And this is not an excuse, no. But it is a way out of the supreme weakness hobbling this idiom supreme: there’s absolutely nothing to prevent a writer from taking a protagonist and the reader bobbing along behind through a portal and on a quest that traverses an argued, arguable fantasyland, one where the questions one asks of the garrulous wizards, the interruptions one makes in the stories they try to dictate, are themselves important bildungstones, are themselves crucial steps on the road to the Crystal City of redemption and restoration.

(The trick of course is that the bedrock grammar of fantasy—that’s Clute, we’ll get there, trust me—would set you on a road to redemption and restoration, which irresistably implies that the questions asked will ever have final, true, correct answers; if you aren’t careful, you’ll just end up shifting the mantle of diktat from garrulous wizard to impertinent protagonist. —I never said it would be easy.)

But even if one doesn’t, even if the book one is reading hasn’t come anywhere near this ideal, well: it’s still a book. And the street will always find its own meanings in books. The most univocal, didactic, imperiously railroaded books can’t help but be polysemous; for fuck’s sake, they’re books.

And as for maps—

Recruit them all you like. Metaphorize and moralize until the very tectonic plates groan beneath the weight of your intentional fallacies. Make the road from Here to There through those Fields Beyond as straight and clear a track as you like. The thing about maps is no matter how simple or naïve they are they can’t help but hold more than you put into them. It’s the nature of maps. Even if it’s just the words Here there be Dragonnes. —Even if it’s just blank space surrounding the railroad track you’ve laid! Hell, sometimes blank space is the most evocative of all.

Go back and look at Papa Tolkien’s map again—

—and forget for a moment the too-obvious sweep of narrative laid out before you from Eriador through Gondor to Mordor. Haven’t you always wondered, lying on your stomach, map unfolded carefully carefully from the endpapers and laid out on the carpet before you, haven’t you always wanted to know what the beaches of the Sea of Rhûn were like, this time of year?

So. Yeah. Maps. Or anyway an intemperate discourse spawned by an offhand remark about maps, and their use and, well, misuse.

Baby steps. —It’s a start.

I’m going to leave you with one more map, an ur-map, if you will; the map, really, of fantasyland as she is wrote, or at least as I’m going to be playing with it for a bit, here:

Of course, a map really benefits from having a key. —It’ll come.

The Great Work.

The time my mother slapped me?

I was a junior in high school. Seventeen? Maybe. I don’t remember what it was I wasn’t to be allowed to have done, but I was complaining about it, bitterly, vociferously, rounding it out with the rising plaint of it just isn’t fair!

Life isn’t fair, she said, exasperated.

That’s no excuse! I snapped.

Pop!

What underpins all of the above is the idea of moral expectation. Fantasy, unlike science fiction, relies on a moral universe: it is less an argument with the universe than a sermon on the way things should be, a belief that the universe should yield to moral precepts.

Which isn’t what happened at all. —Oh, I was complaining about something; I was a teenager. And she’d told me more than once (but not that much more) that life just isn’t fair. And I wanted to say something in response, of course I did; I was a teenager. But if I ever managed to mutter anything at all I doubt it was so pithy. No, the time she slapped me I don’t even remember what she said, or I said. I just remember standing there, in the kitchen of the farmhouse outside of Chicago, the sting, the vague sick flutter in my belly and the half-swallowed grin of embarrassment, the acknowledgement that you know I’d probably deserved what I’d just got, but.

So I lied, just now. —But you know what they say about writers.

I’m not about to talk about it over there; over there, there’s whole words I can’t even spell out for fear of breaking—something. (Like the song says, as soon as you say it out loud they will leave you.) —But I have to talk about it somewhere. When I started to write it it was ten years ago and what we called the thing it was then was completely different than the thing we call by that name now. Used to be it was Eddi and the Fey concert T-shirts; now it’s tramp-stamped werewolves, and is that a bad thing? A good thing? A class thing? A get-off-my-lawn thing? Actually maybe not a different thing at all? —I don’t know, but I think maybe something got written out from under my feet, and it might be a good idea to figure out what it was before I land.

—And also there’s Mendlesohn, and Clute; Clute and Mendlesohn.

Which is not to say they’re wrong, my wanting to hash it all out like I want to. I mean, of course they’re wrong; they’re working with models. All models are wrong. But some are useful, and I haven’t yet figured out whether, or which.

Hence, the Great Work. Limned and primed.

And I will spit on your grave.

In 2006, my attention (such as it is) was captured by the story of one David H. Brooks, who hired 50 Cent and Don Henley and Stevie Nicks and Ærosmith to play his daughter’s bat mitzvah with the profits he made from a sweetheart deal selling inadequate supplies of substandard body armor to our sub-minimum-wage soldiers in Iraq. —How inadequate and substandard? Studies demonstrated that 80% of Marine casualties with upper body wounds could have survived with better (or any) armor. —How sweet? When that study was leaked, soldiers who’d scrimped and saved to buy their own superior armor were suddenly ordered to leave it home, to avoid any possible hurt feelings on the part of a certain David H. Brooks.

And then it receded into the mists of who the fuck can possibly do a damn thing about it? —Why, even today, when a progressive regime has finally triumphed over the forces of evil to take both cameras and the White House itself, a two-year investigation by one of our preëminent journalistic organs that demonstrates beyond the shadow of a doubt the staggering waste and corruption endemic to the shadow cabinets that are tasked with keeping us safe inspires little more than yawns. —How much worse our apathy and despair in the deeps of the Bushian aught-naughts! What chance had any of us then against such a banal kernel of evil as this David H. Brooks?

And so I let it go. What more was there to say?

—Today, I followed a cryptic link from William Gibson’s Twitter feed, and I read this article with a mounting sense of—well, I’m not sure what the word is. But:

Several years ago, David H. Brooks, the chief executive and chairman of a body-armor company enriched by United States military contracts, became fixated on the idea of a memory-erasing pill.

It was not just fanciful curiosity. A veterinarian who cared for his stable of racehorses said Mr. Brooks continually talked about the subject, pressing him repeatedly to supply the pill. According to Dr. Seth Fishman, the veterinarian, Mr. Brooks said he had a specific recipient in mind: Dawn Schlegel, the former chief financial officer of the company he led until 2006, DHB Industries.

There is no memory-erasing pill. And so Mr. Brooks sat and listened this year as Ms. Schlegel, her memory apparently intact and keen, spent 23 days testifying against him in a highly unusual trial in United States District Court on Long Island that has been highlighted by sweeping accusations of fraud, insider trading, and company-financed personal extravagance.

DHB, which specialized in making body armor used by the military in Iraq and Afghanistan, paid for more than $6 million in personal expenses on behalf of Mr. Brooks, covering items as expensive as luxury cars and as prosaic as party invitations, Ms. Schlegel testified.

Also included were university textbooks for his daughter, pornographic videos for his son, plastic surgery for his wife, a burial plot for his mother, prostitutes for his employees, and, for him, a $100,000 American-flag belt buckle encrusted with rubies, sapphires and diamonds.

And—it isn’t schadenfreude, no; this is something colder, older; a little frightening, really: I went and poured myself a shot of bourbon to dull the edge a bit, but then I went and read it again:

Mr. Brooks, who his lawyers have said is in a “tenuous emotional state,” has watched much of the proceedings with glassy eyes and a nervous demeanor.

They straight up just lost nine billion dollars of our money in saran-wrapped bundles dropped in the dust of Iraq.

They’re coming for Social Security, the one thing the Republicans couldn’t wreck when they were running the show, because we just can’t afford it anymore.

It may not be enough compensation to one day use the last of the money in my pocket to hie myself to some Long Island cemetery, there to spit on the grave of this particular David H. Brooks.

It’ll probably have to do.

Things to keep in mind:

The secret of courtesy.

“—I imagined that a man might be driven to despair by all the ugliness he had seen and want to see some unprompted dazzling act of goodness. I think this may not have been right. What I find is that if you deal with bad people for long enough you treasure even trifling acts of courtesy. If I go to a café and order an espresso, I’m charmed, disarmed, speechless with gratitude if the waitress brings an espresso.” —Helen DeWitt

Ichorous, squamous, and rugose.

“I would have given a lot to be at Rush Limbaugh’s wedding last night, where Elton John (his fee a reported 1 million bucks) performed for America’s leading homophobe, and not only because I would have enjoyed that moral dichotomy. I imagine the event to have been more rite than celebration, a frog on a throne, something darker than blood flowing from the champagne fountain, some tincture of BP spill mingled with something more Lovecraftian, a conjunction of Bacchanalian and Bactrian purposes and flavors. I’m certain it was just the usual bad taste scenario, overweight men flirting with women half their age, a toga party for grown ups, as we’ve seen before with certain corporate entertainments; but you can’t completely disassociate the idea of ancient evil from Limbaugh’s buffoonish act. He’s the clown at the party of the damned, dressed in a froggy zipskin suit and playing with a string of mummified human hearts, flicking out his whiplike tongue to snag Viagra from a crystal bowl.” —Lucius Shepard

Dear universe:

Overheating and crashing my computer moments after my first post in months to a dormant blog may seem to you the height of wit, but trust me. Nobody’s laughing down here. (Digging out from under as we speak. Further bulletins etc.)

What comes next—

Well. Now that we’ve driven away all but the most diehard adherents, what say we finally get the real work under way?

“It wasn’t supposed to be like this.”

Hi, I’m Lorne Michaels, the producer of Saturday Night. Right now, we’re being seen by approximately 22 million viewers, but please allow me, if I may, to address myself to just four very special people—John, Paul, George, and Ringo—the Beatles: Lately there have been a lot of rumors to the effect that the four of you might be getting back together. That would be great. In my book, the Beatles are the best thing that ever happened to music. It goes even deeper than that—you’re not just a musical group, you’re a part of us. We grew up with you.

It’s for this reason that I am inviting you to come on our show. Now, we’ve heard and read a lot about personality and legal conflicts that might prevent you guys from reuniting. That’s something which is none of my business. That’s a personal problem. You guys will have to handle that. But it’s also been said that no one has yet to come up with enough money to satisy you. Well, if it’s money you want, there’s no problem here.

The National Broadcasting Company has authorized me to offer you this check to be on our show—a certified check for $3,000. Here it is right here. A check made out to you, the Beatles, for $3,000. All you have to do is sing three Beatles songs. “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah.” That’s $1,000 right there. You know the words—it’ll be easy.

Like I said, this is made out to the Beatles—you divide it up any way you want. If you want to give less to Ringo, that’s up to you—I’d rather not get involved. I’m sincere about this. If this helps you to reach a decision to reunite, it’s well worth the investment. You have agents—you know where I can be reached. Just think about it, okay? Thank you.

—Lorne Michaels, Saturday Night Live, 24 April 1976

Gloriosky—!

Oh, I see—oh, I get it—

Though she’s still a little stronger on the see it than the get it. We’re working on that. —Taran Jack Manley, one year and one day old, at the Oregon Coast Aquarium.

“You can tell him by the liberties he takes with common sense, by his flashes of inspiration, and by the fact that sooner or later he brings up the Templars.”

So, right: the default response to a post from John C. Wright, then, turns out to be exactly the same as the default punchline to a New Yorker cartoon. (—And I have to keep reminding myself: this is from the intellectual end of the rump.)

Little things.

It’s not the sum total of what I’ve been up to, or where I’ve been, but I can’t stop listening to this ever since Joshin pointed it out. —I mean, I’ve also been writing, and I haven’t read a news feed in, what is it, three weeks? Four? Something’s happening, I’m just not sure what.

Important events, and important ideas.

Oodles of channels of 24-hour news, moldering reams of newspapers that will not die, 127 goddamn feeds in my goddamn Google newsreader, and I’m only now finding out that Utah Phillips died sometime last year? —Somebody’s priorities are way the hell out of whack.

Free jazz

Never should have played her that Albert Ayler song.

It’s not so hard to be politically correct. All you have to do is not be an asshole.

“‘I think that Nabokov often tries to be inhumanly secure, and confident, and happy, and unregretful,’ Wood observes. ‘If he pulled that off, he would be a monster. It’s a fine thing to try—and an even finer thing to fail.’” —Lev Grossman, “The gay Nabokov”