Magical white boy.

Oh, hell, let’s chase the red herring for a minute. I’ve got time; I’ve got nothing but time. —So: no. Morpheus is not a magical negro. If nothing else, his touchingly stubborn faith in Neo, which sets him at odds with the magical Oracle, which causes us to doubt him (though we never doubt he’s right: Neo must be the One—look at his name!), and which even causes him to doubt himself—this grants him a degree of agency and protagonism that sets him apart from the mere role of wisely aiding and abetting Neo’s enlightenment. (To say nothing of his captaincy, his popular acclaim in Zion, or the fact that he’s the one who lives to tell the tale—)

So: the One True Neo, a man with almost no past, prone to criminality and laziness, inwardly disabled by his shyly geeky nature, hated as a hacker by the powers that be, granted a terrible power so close to the very nature of things yet tempered by his need to help others, ultimately sacrificed, and all to aid Morpheus in realizing his dream—

Well, yes. That’s why the movies, flawed though they indisputably are, nonetheless have the power they have.

But I wasn’t really thinking about the red herring. I was thinking about Mercutio, and I was thinking about Nick.

—Why was I thinking about Mercutio? Right. Because we’d just finished the second season of Slings and Arrows, with its hilarious production of Romeo and Juliet running under and around the A-plot of Macbeth. Why was I thinking of magical negroes? Because I’d stumbled over MacAllister’s LiveJournal, and the most recent entry over there is a nice-enough trip through the trope. And why was I thinking of Nick?

Well, first, Mercutio; specifically, given the confluence of topics, Harold Perrineau’s, in the deliriously ludic Baz Luhrman production. Ostensibly Romeo’s foil, Perrineau’s Mercutio practically foils the whole damn film, othered to his very gills: the only black character, his gender bent in an otherwise rigidly stratified world, his sexuality—well. Even the lightest brush of those buttons with Mercutio—witty, articulate, prancing Mercutio, always a snappy dresser—leaves little room for doubt. —Forever outside the discourse of both those houses, he pushes and pulls and chides his charge until Romeo sees the light and gets off his goddamn ass, and as far as magic goes, well. Queen Mab, bitches. Those drugs are quick.

But hard as they might push in that direction, and as much power as they might arguably draw from the trope, and despite his Act III Scene 1 sacrifice, there’s no way in hell or out of it that Mercutio could ever be anyone’s magical negro.

(A conscious piss-take? I doubt it; I highly doubt it, if for no other reason than Spike Lee’s eponyming talk came five years later. —But Uncle Remus has been with us for a long, long time. Even in Australia.)

Nick, of course, Chris Eigeman’s Nick, is the Mercutio of Metropolitan, othered by his cheerfully chilly snark, his abiding concern for times and fashions past, his detached perspicacity—though perched in the very catbird seat of privilege, he is nonetheless, within his own context, his insular circle, despised; though his power is mighty (he creates a person from whole cloth, like New York magazine) and his scorn withering (ask a bard what terrible magic satire can wreak), he does little beyond push and pull and chide his Romeo, Tom Townsend, over the barest threshold of the story. (He does also insult a Baron, and start a cha-cha.) —And though he isn’t sacrificed, per se, he does abruptly leave the story toward the end of the second act (of three, of course, not five), marching stoically off to his comically supposéd doom.

But much as it might tickle me to push this WASP in that direction, there’s no way in hell or out of it that Nick could ever be a magical negro.

And not because he’s so very, very white. Well, yes, of course, but—

Nick’s a foil, like Mercutio: slipped under the gem of the protagonist to catch the light and throw it back, up and through the protagonist’s facets, the better to shine for our delectation; necessarily subordinate to the protagonist because it’s all about the protagonist. Isn’t it? —They are othered because the protagonist is by definition normal, and they must stand in contrast. They leave so suddenly because the protagonist, having been pushed, must in the end do it all alone. It is, after all, the protagonist’s story.

Yet ask an actor who they’d rather play.

There are foils that disappear behind their gems, that bow and scrape their way across the stage, that take so literally the story-mechanics of their function—to assist the protagonist, buff and polish them till they shine—that they reify those rude mechanics within the story itself, black-garbed kabuki janitors shoving the machina in place for the fifth-act emergence of a pure white deus, and they perform these tasks with little more than a wide wise smile to hint at a there in there, somewhere. And there are settings so rich and strange and wondrous that the very question of who is a protagonist and who isn’t becomes a trick of where your eye happens to light first, and what you make of it. —Nick and Mercutio fall within that spectrum (there is no doubt as to the protagonists of their stories: not them), yet much closer to the one end than the other: no mere enablers, but so very much themselves, so selfish that they’d never be mistaken for the help.

(And because they stand so flashily in contrast to protagonists who must, as noted, be so damned normal [though admittedly not too normal, in either case], a little of the life of the proceedings can’t help but leak out when they leave. There’s a lesson there, too: like all good blades, this stuff cuts both ways.)

—One final digressive note, which draws a little on the related though much less prevalent trope of the magical faggot (think for a moment of the queer eyes buffing and polishing their protagonist; now let’s move on), and specifically the o’erwhelming need for queer foils to die in order to balance out on some inhuman scale the racy transgressions they commit to foil whatever they’re foiling; more specifically, the storied death of Tara, from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which Mac (most specifically) brought up in passing at the end of the post that’s one of the wellsprings for this one: well. It’s at once rather a bit less complicated than that, and rather a bit more.

The one true only.

And so we return and begin again.

You know, human batteries aside, I enjoyed The Matrix well enough right up to the very end, you know, the Nebuchadnezzar’s blowing up all around them, those electric jellyfish beating their way in, Neo lying flatlined in the cradle, Hugo Weaving with his gray-flannel smirk, and Trinity leans over Neo and says something like, “Neo—I’m not afraid anymore! The Oracle told me—”

Yes?

“—I would fall in love, and that man, the man I loved, would be the One. So you see, you can’t be dead, you can’t be—because—”

Oh, no no no no no. That’s not what the Oracle told her, dammit. Should have told her. Could have. Would have. What the Oracle should have told her is what the Oracle should have been telling every-damn-body:

You’re not the One. Not yet. Sorry, kid. Looks like you’re waiting for something. Your next life, maybe. Better luck next time.

Still bugs me, thinking about that.

Well, the human batteries, and that shoot-out in the lobby. Gratuitously nasty round of best-man-fall. That little gesture to fix the sunglasses, trying to remind us it’s only a game. —Doesn’t work, somehow.

Wait a minute—

“I say, old chap, could you explain something to me?”

“I suppose.”

“You see, well, it’s just—this wall we’re building. Of raw meat. The flensed cow-carcasses and such. It’s not I’m complaining, no, of course not, far from it, but it’s such an odd thing to be doing.”

“You want to know why we’re building this wall of raw meat.”

“Bingo! Hit it in one.”

“Well, the tigers, of course.”

“Oh, yes. Of course. The tigers.”

“It’s to keep us safe from the tigers.”

“You know, now the you mention it, I believe I’d heard something to that effect. All part of the initiative, right? Like the duct tape and the surveillance and the torture and that ridiculous television program. Of course. The wall of raw meat. Capital.”

“Well, do you see any tigers around hereabouts?”

“Do you know, I think I have? Why, one carried off poor Maybelline just yesterday. Stacking some butchered pigs on the south side, and it just swooped out of the jungle and with one gulp— Terrible thing. And one does hear them prowling about out there, roaring now and again, much more than one ever used to! Doesn’t one?”

“Precisely! So hadn’t you better keep building this bloody damn wall?”

Chin-chin.

Just taking a moment to note that while Ethan Rayne rates a rather fully fledged entry in Wikipedia, Willoughby Kipling gets jack squat.

Footnote to a prior conversation.

Dread by its nature anticipates; therefore, “anticipatory dread” is something of a redundancy. —Apologies.

We only sing about it once in every twenty years.

Everybody’s linking up the “4th of July,” but the only X song for me today is “See How We Are.” And the best post for seeing just that today is Rick Perlstein’s.

What’s the argument? That conservatives’ tragic misunderstanding of freedom has produced exactly what Goldwater feared most: stifling the energy and talent of the individual, crushing creative differences, forcing conformity—and, yes, even leading us to despotism (and I’m not talking about habeus corpus or NSA spying). By methodically undermining the public’s will and ability to underwrite the public good, systematically accelerating economic inequality, and making turning oneself into a commodity—“selling out”—the only possible route for young people who wish a reasonably secure middle class existence, conservatives killed liberty. The canary in the coal mine is the death of young people’s “freedom to live adult lives typified by choice rather than economic compulsion.”

I think I made a decision at some point in the past few days of McCloud Madness; I think I’ll be the better for having done so, soon enough. We’ll see. —Further bulletins as events warrant.

Burned all my notebooks. What good are notebooks?

“We have Atlantis launching sleeper cell terrorist attacks, we have the Inhumans declaring war on humanity and wanting to take over the world, we have mutantkind facing extinction and infighting, America becoming a police state because superheroes might accidentally blow up a school full of kids, and by the way, your best friend or anyone you know might be an alien invader undercover. There’s an incredible and depressing lack of openness to ‘the other’ in Marvel’s books, these days; nothing is seen as new or different or unusual in a good sense, because everything that isn’t ‘us’ is a threat (as opposed to even being a potential threat). Whatever happened to the days of The Impossible Man appearing and aliens being goofy nuisances? Or Spider-Man being misunderstood and really a good guy, not a public menace, you know? There used to be a time where it was awesome (in both senses of the world) that there was a race of superhumans living on the moon, instead of it being another band of people who want to kill us. Yes, there are a few exceptions (Iron Fist and Fantastic Four come to mind), but overall: Is it really post-9/11, post-Afghanistan invasion and post-Iraq civil war insularism informing what the Marvel writers are coming up with, or something else? And, either way, is there any way that optimism and, well, good fun could come back to these characters again?” —Græme McMillan

I’m pretty sure there’s a Mountain Goats song about this. I’m equally sure it doesn’t apply.

Last night was the second night of the Spouse’s sleep study; last night was the second night in as many weeks that my plan to spread out across the whole queen-sized bed was thwarted by Beezel, frantically burrowing under the sheets, looking for the other human who just had to be here somewhere. —And this morning I once more made a full dam’ pot of coffee before remembering I was by myself and couldn’t possibly drink it all.

All that is necessary for evil to triumph.

“The attitude among the Democrats and the media now seems to be that, hmm, maybe if we keep our fingers crossed we won’t need a government for anything until 2009, and if we just wait until then, the next president can get everything running again just in the nick of time.” —Phil Nugent

“I also happen to think she needs to eat a sandwich and cover up a bit.”

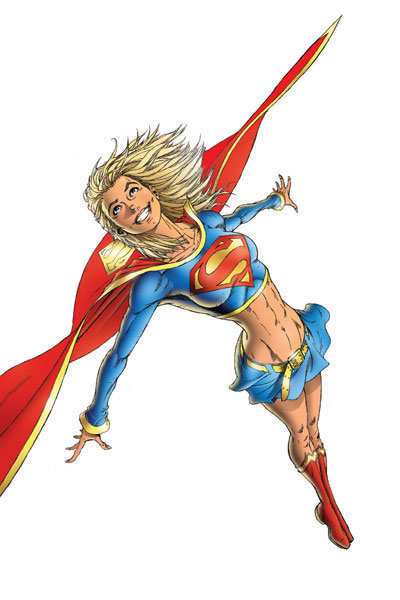

From this:

to this:

It’s not nearly Scott Pilgrim enough, but still. A good step taken.

I am interested in your product or service, and I’d like to hear more.

A quote from Trilling; head over to Kugelmass for context:

As we read the great formulated monuments of the past, we notice that we are reading them without the accompaniment of something that always goes along with the formulated monuments of the present. The voice of multiplication which always surrounds us in the present, coming to us from what never gets fully stated, coming in the tone of greetings and the tone of quarrels, in slang and in humor and popular songs, in the way children play, in the gesture the waiter makes when he puts down the plate, in the nature of the very food we prefer… And part of the melancholy of the past comes from our knowledge that the huge, unrecorded hum of implication was once there and left no trace—we feel that because it is evanescent it is especially human. We feel, too, that the truth of the great preserved monuments of the past does not fully appear without it.

Chivalry, being dead—

The scene: it’s 1965. Travis McGee, that amiable skeptic, that waterfront gypsy, thinking man’s Robin Hood, killer of small fish, ruggedly sexy boat bum, that big, loose chaser of rainbows, that freelance knight in slightly tarnished armor, Travis McGee has picked up an old friend, Nora Gardino, who puts on a deep shade of wool, not exactly a wine shade, perhaps a cream sherry shade, a fur wrap, her blue-black hair glossy, her heels tall, purse in hand, mouth shaped red, her eyes sparkling with holiday for their date. He takes her out to the Mile O’Beach for steaks and cocktails in the Captain’s Room and when dinner’s over and the old-times talk is just about spent he tells her why he’s called her for the first time in a year or so to take her out to dinner: Sam Taggart, the man who left her hard and bad and stupid as hell three years before and lit out for parts unknown is coming back, and it turns out he is still carrying a torch, as big as the one she’s got in her own hands.

So Nora’s pole-axed, wheels around, drops her head between her knees. Trav motions the maitre’d over to bring some smelling salts. Out in the parking lot, she leans against a little tree and pukes up the steak. He takes her home in his electric blue Rolls Royce pickup truck to his place, his houseboat, the Busted Flush, Slip F-18, Bahia Mar, Fort Lauderdale, where he turns up the heat (it’s February, hence the fur in Florida) and makes her a mild drink and they settle down to talk about how maybe Sam let her catch him in bed with her shop assistant a month before the wedding because maybe he’s the sort of guy who’s afraid of being tied down, how a real live complete woman can be a scary thing, how even if maybe she thinks she came on too strong she has to be what she is, and how Trav heard from him and knows he’s coming back, and how he’ll set it up so she gets to see him again. And as the talk winds down again, he says,

“Don’t plan anything. Play it by ear, Nora. Don’t try to force any kind of reaction. It’s the only thing you can do.”

“I guess,” she said. She gave me a shamefaced look. “This is idiotic, but I’m absolutely ravenous.”

“Nora, honey, you know exactly where everything is, including the drawer where you’ll find an apron.”

“Eggs? Bacon? Toast?”

“All there. All for you. I’ll settle for one cold Tuborg. Bottom shelf. No glass, thanks.”

Bruises and roundhouses.

This may just be a pattern in search of a theory that is itself in search of a problem, but it struck me in the shower and hasn’t gone away, and so I give it a wipe and a polish and set it down before you. “It” being: the notion that there might be if not an essential difference between the pulp heroics of prose and the pulp heroics of comics (because, let’s face it, everything is essentially the same dam’ thing) then perhaps a perceptible difference: what is heroic in a prose pulp hero will tend or drift or gesture toward the done-to, the withstood, the survived, the masochistic; what is heroic in comics pulp will tend or drift or gesture toward the done-by, the delivered, the unleashed, the sadistic.

Not to freight our gestures or drifts or looks too heavily or anything. Pattern, theory, problem. —But think of James Bond (in the books), think of Travis McGee: the scars they display; the pain suffered so exquisitely during and after every fight. Think of Spider-Man, think of the Batman, think of the balletic spins and kicks, the terrible punches, the bodies in motion.

There’s nothing sinister about this, no more than there’s anything original: it’s merely the difference in artistic technologies employed. One’s hand fitting itself to one’s tools. With prose, all you have are words, and the reader’s sensorium, and the changes and echoes you can ring by banging the one against the other: and so for effect you’re going to focus on making the reader feel (and see, yes, and hear and smell and taste, too) what’s happening. You’re going to do to them, and if you’ve got a protagonist in the way, you’re going to do it through them. —Whereas with comics you’re handing the reader what they’re seeing (with certain shorthands and gestures and signs and symbols to be interpreted according to various rules, yes, we’re still reading, after all); it’s pretty much the preoccupation with what it is you’re doing, and doing just looks ever so much cooler than being done to. And so.

And of course there’s all sorts of spoiling overlaps, and yes Wolverine is the best there is at soaking up yadda yadda, and Bond is himself a sadistic bastard, but then he’s also in the movies a lot. —This is hardly a hard and fast genre rule unwritten or otherwise; it’s hardly an idiomatic necessity. It’s a reflexive tendancy. It’s a pattern, in search of a theory, wondering whether there’s a problem with reflexively, unthinkingly, turning to doing, or being done to, in order to drag the reader from the phenomenal to the sublime. Probably not. (One so dislikes being judgmental.) But like I say, it hasn’t gone away. Give it a poke. See if something happens.

Cui bono?

“‘A group of boys I know were thinking of going to the Lloyd Center on the max to see 28 Weeks Later on Friday night,’ said TJ Browning—a long-time Forum member, this morning. ‘But one of the boys said, “Wait a minute, that curfew thing is going on,” so they chose not to go on Friday night.’ —Browning was, in fact, touting this as a sign of the policy’s success, but to what end?” —Matt Davis

It’s the little things.

Shouldn’t he be saying “Myanmar”?