Wood and silverware.

It’s been five years. So far. Give or take the occasional hiatus.

Cusp.

So I took one of those meme-quizzes the other day, the “Which action-movie hero are you?” quiz. It had to ask a tie-breaking question, which is the first time I’ve ever seen that happen. Couldn’t decide whether I was Indiana Jones, or Captain Jack Sparrow. —I’m not sure how to respond to that.

Woke up strange.

Meant to note this earlier, but what with one thing or another. —Dreamed last night (and while I’m sure I dream as much as the next fellow, I don’t often remember my dreams, so) that I was headed to Michigan to meet someone I can only assume was Lindsay Beyerstein so we could spend the next three months tooling up and down the East Coast, following Michael Bérubé on a book tour. I can only assume it was her because I’ve never actually met Lindsay Beyerstein; I have not, to my immediate recollection, even spoken with her via chat or email. But she had short blond hair and when I asked for something warm to put on (it was cold, you see, in Michigan), she gave me a jet-black hoodie.

Lindsay: I have to apologize for how strangely cold I became. The handwritten note that was slipped under the door when neither of us was looking, the one I grabbed and wouldn’t let you see? Whatever I read there made me suddenly distrust you. But just because I could read it in the dream has nothing to do with whether or not I could actually read it, and some of the questions I was starting to rather belligerently ask were really just me getting frustrated with how much of a jerk I was being and trying to figure out what was really going on. Since I wasn’t telling myself, see.

—We never did get to the East Coast, which is fine, since I’ve never met Bérubé before either, and I’d have no idea what to say to him. Maybe this is why I don’t too terribly often bother to remember my dreams.

A nod from a lord is breakfast for a fool.

Oh, hey, it’s National Delurking Week. Nod away.

D’Souza’s corollary to Godwin’s law:

As an argument with a conservative grows longer, the probability that they will blame you for causing 9/11 approaches one.

If “other” and “others” are before your eyes,

Then a mosque is no better

Than a Christian cloister;

But when the garment of “other” is cast off by you,

The cloister becomes a mosque.

A random trail of breadcrumbs ends unceremoniously at this Pajamas Media piece on “The Islamification of Europe’s Cathedrals,” which asserts (from Los Angeles) with a straight (if pop-eyed, sweat-soaked) face that—

The recuperation of places and buildings that were once mosques or sacred Islamic sites is the primary method employed by Muslims to reconquer Al-Ándalus. So-called moderate Muslims are oftentimes more effective than extremists in gaining concessions because of their attempts to portray Western democracies as intolerant if those countries don’t cede to certain demands. This technique has been used repeatedly in the case of the Córdoba Cathedral.

Meanwhile, they’ve started whispering that Barack Hussein Obama is some sort of Wahabbist Manchurian candidate. —They really have gone around the bend, haven’t they? They really aren’t coming back, are they? I mean, I know this, but Jesus good God damn.

“Sir, prove to me that you are not working with our enemies.”

A lot of people are upset at the fascistic übertones of Sean “Haw Haw” Hannity’s new “Enemy of the State” feature, but what I want to know is this: why the hell is he dressing like Mahmoud Ahmadinejad?

Tipping their hand.

Red is the boldest of all colors. It stands for charity and martyrdom, hell, love, youth, fervor, boasting, sin, and atonement. It is the most popular color, particularly with women. It is the first color of the newly born and the last seen on the deathbed. It is the color for sulfur in alchemy, strength in the Kabbalah, and the Hebrew color of God. Mohammed swore oaths by the “redness of the sky at sunset.” It symbolizes day to the American Indian, East to the Chippewa, the direction West in Tibet, and Mars ruling Aries and Scorpio in the early zodiac. It is the color of Christmas, blood, Irish setters, meat, exit signs, Saint John, Tabasco sauce, rubies, old theater seats and carpets, road flares, zeal, London buses, hot anvils (red in metals is represented by iron, the metal of war), strawberry blondes, fezes, the apocalyptic dragon, cheap whiskey, Virginia creepers, valentines, boxing gloves, the horses of Zechariah, a glowing fire, spots on the planet Jupiter, paprika, bridal torches, a child’s rubber ball, chorizo, birthmarks, and the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church. It is, nevertheless, for all its vividness, a color of great ambivalence.

—Alexander Theroux, The Primary Colors

Red state, blue state: it’s divisive bullshit, an accident of history barely six years old, it’s a goddamn eyeworm, an honest-to-god meme that won’t get out of the way, a map that warps the thing it maps. It’s magic, is what it is. All this business, George Lakoff and his frames, George Bush and his backdrops, David Brooks capitalizing random nouns in a desperate attempt to bottle that Bobo lighting once more, the hoarse, fierce shadowboxing around “surge” or “escalation” that would be grotesque if it weren’t already so weirdly disconnected—it’s all magic, groping for the emblem or rite, the utterance or name that will when written or shown or repeated often enough bring about that change in accordance with will. Some of it works, some of it doesn’t; as usual, it’s the stuff nobody’s trying to make work that works the best. Psycohistory’s still an art, not a science. (Hence: magic.)

—Digby points us to the latest effort of some apprentices to the art: Applebee’s America: How Successful Political, Business and Religious Leaders Connect with the New American Community. Written by a former Clinton strategist, a former Bush strategist, and a former national political writer with the AP, it purports to tell us:

Political commentators insist that the nation is a collection of “red states” (Republican) and “blue states” (Democrat). The reality is that America is a collection of tribes—communities of people who run in similar lifestyle circles irrespective of state, county, and precinct lines.

And there’s some stuff about Navigators (“otherwise average Americans help their family, friends, neighbors, and coworkers negotiate the swift currents of change in twenty-first-century America”) and how fundamental political decisions are made with the gut and not the head and how the authors have cracked the twenty-first century code with their “LifeTargeting” [sic] strategies, etc. etc. —But at least they’ve abandoned red-state blue-state, right? Faceted their analysis into tribes? Brought some nuance into the picture, beyond those two drastically simplified tribes, red and blue?

Yup. There’s three.

Red. Blue. And Tippers.

No. Not otherwise entertaining Second Ladies with an inexplicable mad-on against explicit pop music. People who, like, tip, from red to blue. And back. Get it? Tippers?

—If you’re curious as to how you’d rate in this 2004-level political analysis, there’s a quiz. I scored as a member of the Red tribe. (Apparently, Dr. Pepper, Audis, TV Guide, and bourbon are all more Red than Sprite, Saabs, US News & World Report, and gin.) —I’m thinking their “LifeTargeting” maybe needs to go back to the drawing board for a bit.

Now, I’m not knocking dualism. Dualism isn’t always bad; like any tool, sometimes it’s useful, sometimes it isn’t. With a book like Applebee’s America, there are, indeed, two tribes: those the authors (and the publisher) are trying to reach, and those they couldn’t care less about. A quick scan of the website makes it clear who’s us and who’s them in this particular case:

Their book takes you inside the reelection campaigns of Bush and Clinton, behind the scenes of hyper-successful megachurches, and into the boardrooms of corporations such as Applebee’s International, the world’s largest casual dining restaurant chain. You’ll also see America through the anxious eyes of ordinary people, buffeted by change and struggling to maintain control of their lives.

This isn’t political or sociological analysis. It isn’t even pop sociology. It’s an I’ve Got Some Cheese book. “Applebee’s America cracks the twenty-first century code for political, business, and religious leaders struggling to keep pace with the times,” says so right on the website. —And if you see yourself as a political, business, or religious leader in this twenty-first century, looking out on the ordinary people from behind the scenes in the boardrooms, well, they’ll gladly hand you a neatly bound stack of printed paper in exchange for your money.

—Nor am I knocking the idea of tribes, or guts. Psychology Today has a mildly interesting follow-up to the “Crazy Conservative” study of mumblety-mumble spin-cycles ago, and really, the basic idea that conservatism stems from fear and uncertainty, that liberalism and tolerance are best nurtured by stability and confidence, these are hardly controversial ideas, when you stop and think about it. (In the terms I’ve chosen, yes. Hush.) —For those who want something boiled a wee bit harder, there’s the work of Mark Landau and Sheldon Solomon, on page 3, which gets interesting about here:

As a follow-up, Solomon primed one group of subjects to think about death, a state of mind called “mortality salience.” A second group was primed to think about 9/11. And a third was induced to think about pain—something unpleasant but non-deadly. When people were in a benign state of mind, they tended to oppose Bush and his policies in Iraq. But after thinking about either death or 9/11, they tended to favor him. Such findings were further corroborated by Cornell sociologist Robert Willer, who found that whenever the color-coded terror alert level was raised, support for Bush increased significantly, not only on domestic security but also in unrelated domains, such as the economy.

Old hat, yes, to anyone who’s been paying any attention at all, but how many of us really do? —You have to turn to page 5 for the punchline.

If we are so suggestible that thoughts of death make us uncomfortable defaming the American flag and cause us to sit farther away from foreigners, is there any way we can overcome our easily manipulated fears and become the informed and rational thinkers democracy demands?

To test this, Solomon and his colleagues prompted two groups to think about death and then give opinions about a pro-American author and an anti-American one. As expected, the group that thought about death was more pro-American than the other. But the second time, one group was asked to make gut-level decisions about the two authors, while the other group was asked to consider carefully and be as rational as possible. The results were astonishing. In the rational group, the effects of mortality salience were entirely eliminated. Asking people to be rational was enough to neutralize the effects of reminders of death. Preliminary research shows that reminding people that as human beings, the things we have in common eclipse our differences—what psychologists call a “common humanity prime”—has the same effect.

Ask us to consider carefully. Remind us of the things we have in common. It’s apparently that simple. Which doesn’t mean it’s easy. And any book that was actually about how to lead and build and make the most would talk about how to do that, and how to keep on doing that.

Anything else is magic, and as any real magician will tell you, magic’s a great way to make some money—but it’s a lousy way to chop wood and carry water.

Blue is a mysterious color, hue of illness and nobility, the rarest color in nature. It is the color of ambiguous depth, of the heavens and of the abyss at once; blue is the color of the shadow side, the tint of the marvelous and the inexplicable, of desire, of knowledge, of the blue movie, of blue talk, of raw meat and rare steak, of melancholy and the unexpected (once in a blue moon, out of the blue). It is the color of anode plates, royalty at Rome, smoke, distant hills, postmarks, Georgian silver, thin milk, and hardened steel; of veins seen through skin and notices of dismissal in the American railroad business. Brimstone burns blue, and a blue candle flame is said to indicate the presence of ghosts. The blue-black sky of Vincent van Gogh’s 1890 Crows Flying over a Cornfield seems to express the painter’s doom. But, according to Grace Mirabella, editor of Mirabella, a blue cover used on a magazine always guarantees increased sales at the newsstand. “It is America’s favorite color,” she says.

—Alexander Theroux, The Primary Colors

It’s true what they say.

Alabama hot slaw goes with just about every damn thing.

®udy!

Rudy Giuliani has taken a tip from Harlan Ellison and trademarked his name. The Daily News doesn’t make it clear if he’s just slapped a ™ after it, or ponied up the money for a full ®, but I think it’s a mistake to assume as Steve Benen does that this is just about Giuliani’s consulting business. The Trademark Dilution Act became law in October, and it allows an injunction against infringing actions “by reason of dilution by tarnishment, the person against whom the injunction is sought willfully intended to harm the reputation of the famous mark.” Speak ill of Rudy® (or Rudy™), and you’ll be shut down. —Oh, sure, there’s an exemption carved out for “all forms of news reporting and news commentary,” but who the hell knows what that is, anymore?

Is that a 75mm recoilless rifle on your Vespa, or are you happy to see me?

Which is, yes, a Vespa scooter fitted with a 75mm recoilless rifle.

After World War II, there was little money for defense spending while the nations of Europe rebuilt their industry and society. When there was some cash to spend, one had to be creative to stretch it as far as possible. The French probably accomplished the most astounding example of that with the ACMA Troupes Aeról Portées Mle. 56. Deployed with their airborne forces, this was essentially a militarized Vespa scooter outfitted with a 75mm recoilless rifle. Five parachutes would carry the two-man gun crew, weapon, ammunition, and two scooters safely to earth, and the men would load the weapon on one scooter and the ammo on the other, then ride away. More impressively, the recoilless rifle could be fired effectively on the move by the best of the gun crews. Total cost? About $500 for the scooter and the recoilless rifle was war surplus. Were they successful military machines? Well, the French Army deployed about 800 armed scooters in wars conducted in both Algeria and Indochina.

This, for whatever reason, reminded me of this old thread over at Vince Baker’s joint—specifically, this comment:

ROCKING WITH JFC FULLER

There are three things you can do in a fight:

- HURT THE OTHER GUY – how hard can you hit the other guy with your rock/RPG/railgun?

- PROTECT YOURSELF – how hard are you to hit, and how hard a hit can you take?

- MOVE AROUND – how fast can you move, over whatever ground?

The core dilemma: Anything you do to make yourself better at one of these things makes you worse at one or both of the others.

That applies on all scales:

- ”As long as I stay in this ditch, they can’t shoot me! But I can’t shoot back, unless I stand up—which makes it easier for them to shoot me, too—and I can’t move except back and forth in the ditch—unless I get out and run—which makes it easier for them to shoot me and I’ll be moving too fast too aim.”

- ”Men, form a square! Excellent, now Napoleon’s cavalry cannot hope to overrun us. But with men facing all four directions instead of in a line, we can’t concentrate our musket fire against any one target, and if we wanted to march anywhere, we would really move faster in column formation.”

- ”This new tank has impenetrable armor! But that means no engine we can put in it will move it very fast. And if we want to put a bigger gun in it, it’ll be even slower, unless we get rid of some armor….”

- ”Our clan has always been safe in the mountains! If those filthy lowlanders try to attack, we just slaughter them like sheep in the narrow passes! Of course, if we try to attack the lowlanders, they just slaughter us coming out the other end of the passes. And even in a year with little snow, we can barely move warriors from one village to another.”

See how the same iron triangle of tradeoffs repeats itself? The only way out of the dilemma—sometimes!—is higher technology, but even then, once you get the more powerful engine for your tank (or whatever), you just move from your old trade-space to a new, slightly better trade-space.

I suppose because the Mle. 56 is a remarkably unexpected method of squaring this particular iron triangle. But also because I like to imagine the Ilk of Jonah being chased by squads of the dam’ things. —I am, at base, a petty, petty man.

Anyway: into the commonplace book it goes.

The trick is how to find it.

“Jeff Conaway!” I said to myself, stumbling over the name in maybe a Gawker Stalker or something, pegging him by the reference to his Christianity. Now that I have his name, I can go to imdb and scroll down his credits and trust that the name of the show will be self-evident. —I’d forgotten the name of the show, see, and everyone who was in it except the star who was the guy from Grease and later Taxi whose name I could never remember. (Though for whatever reason the whole born-again thing stuck with me.) I don’t even remember the show itself that well, just that it was funny when I was fifteen, and I cared enough about it to hurry back to the hotel room after a swim meet so I could coax the bunny ears into pulling down a relatively snow-free CBS signal. Then they killed it. —And now I learn that most of the episodes were directed by Bill Bixby. Wizards and Warriors. Damn. Everything’s pretty much in this intertubes thing somewhere, isn’t it? (Except, y’know, the actual episodes.)

One state, two state, red state, blue state.

Amanda Fritz makes a pretty good case for Oregon going red in 2008.

Esoteric middlebrow.

“Wild Dance,” Ruslana Lyzhichko; “Illartia (PDX edit),” SpineFolder; “An instrumental work, called ‘pleasant,’ 4th mode,” Hristodoulos Halaris; “Smack Your Lips (Clap Your Teeth),” the Residents; “Summer Vacation,” 林原めぐみ; “Within a Room Somewhere,” Sixpence None the Richer; “ALWAYS,” 田村直美; “Enchanted,” Delirium; “Hebeena Hebeena,” Farid el Atrache; “On droit fin[e] Amor; La biauté,” Anonymous 4.

After the late, great unpleasantness.

I am a Southerner, for all that I’m expatriate—born in Alabama, raised in Virginia and the Carolinas and Kentucky, I graduated high school in John Hughes land and attended a famously liberal arts college on the North Coast of Ohio. Since then, I’ve lived my life in New York and Boston and the Pioneer Valley and Portland, Oregon, and I haven’t spent more than two weeks at a stretch south of the Mason Dixon. (And those stretches are sometimes awfully few and far between.) —But I cook up hoppin’ john for New Year’s, every year (though, apostasic, I make it without the fatback). I taught my Jersey girl how to eat grits and I make my biscuits from scratch. (Food? Don’t laugh. Look to the roots of your own tongue.) —I’m haunted by the smell of magnolia blossoms, plucked and left in a drinking glass on the mantelpiece. (They smell lemony, the same way apples do.) Long pine needles crushed underfoot, dry, not wet and silvery grey; evergreens burnt brown by the sun. I always forget until I see it from the window of the plane, how red the dirt is, scraped up, laid shockingly bare in circles of development scars that will always ring Charlotte: how wrong it looks, how raw. It’s not the color the earth is supposed to be. It’s alien; I’m home.

For a couple of weeks, at most. And then.

(“You will find no other place, no other shores,” says C.P. Cavafy. “This city will possess you, and you’ll wander the same streets. In these same neighborhoods you’ll grow old; in these same houses you’ll turn grey.”)

—If you aren’t Southern, I don’t know that I can explain the little thrill I felt when I saw the motto for the Levine Museum of the New South: “Telling the story—1865 to tomorrow.” Shock is hardly the word. Frisson even seems too strong. It’s a stifled giggle; a flash of a grin, at something you’d’ve done yourself, but never would have thought to do. It hardly seems worth mentioning, but—well, maybe the About Us page will bring it into focus for the Yankees among us?

What is the New South?

The New South means people, places and a period of time — from 1865 to today. Levine Museum of the New South is an interactive history museum that provides the nation with the most comprehensive interpretation of post-Civil War southern society featuring men, women and children, black and white, rich and poor, long-time residents and newcomers who have shaped the South since the Civil War.

New South Quick Facts

- A Time—The New South is the period of time from 1865, following the Civil War, to the present.

- A Place—The New South includes areas of the Southeast U.S. that began to grow and flourish after 1865.

- An Idea—The New South represents new ways of thinking about economic, political and cultural life in the South.

- Reinvention—The New South encompasses the spirit of re-invention. The end of slavery forced the South to reinvent its economy and society.

- People—The New South continuously reinvents itself as newcomers, natives, immigrants, visitors and residents change the composition and direction of the region.

To say that you are about the South, but dismiss the antebellum—not to forget, because who can forget, not even to repudiate it, but to wave it off as no longer important to the South you want to look at, here and now— Don’t throw out the cotton and the rice, the pastel dresses and grey uniforms, the stars and bars and whips and chains. Those things are all still very much alive and kicking. But cut out the thing that props them up, the hollow rites, the archly wounded pride; blithely (if a little self-consciously) announce you’re leaving the Civil War well enough alone, to all the many other hands that want it; you will turn your attention to everything else, and watch it all fall into some saner perspective—1865 to tomorrow—

(“How long can I let my mind moulder in this place?” says C.P. Cavafy. “Wherever I turn, wherever I happen to look, I see the black ruins of my life, here, where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them, destroyed them totally.”)

The Levine Museum of the New South is currently hosting an exhibit called “Families of Abraham.” Eight photographers spent over a year with 11 families in the Charlotte area—Christian families, Jewish families, Muslim families—recording their holidays and everydays, putting the photos together to demonstrate that when you set aside the different words we’ve each plucked from the same shambolic Book and just look at the people, going about their lives, well, under the chadors and yarmulkes and double-knit blazers we’re all, y’know, the same. Basically.

Which is why, given the way things currently are, what with the Pragers and the Goodes and the Qutbs, this show is important. —But it’s not why it’s important to me.

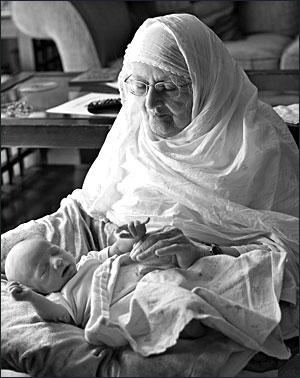

That’s a photo (by my mother, which is why the show is important to me, yes, but), a photo of Basheer Khatoon with her great-grandson, Raahil, taken in the home she shares with her son, a Charlotte cardiologist.

My South—the South in my head, the South I came from—doesn’t have a Basheer Khatoon. But there she indisputably is. Alien—and yet, from all the years I’ve spent since and elsewhere, heimlich. The world has come to the South; the South—my South—is becoming part of the world.

No matter where we go, there we are; we find no other place, no other shore. We wander the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods. —But those streets change.

Why you all so kip?

I mean, really: how many people can ego-surf on Urban Dictionary?

Chillin’ with Frank & Ernest.

Congratulations, by the way, to R. Stevens, as Diesel Sweeties adds the daily newspaper to its burgeoning media empire.